Articles

Paretotopian Goal Alignment

Paretotopian Goal Alignment

What if humanity suddenly had a thousand times as many resources at our disposal? It might make fighting over them seem like a silly idea, since cooperating would be a safer way to be reliably better off. In this talk from EA Global 2018: London, Eric Drexler argues that when emerging technologies make our productive capacity skyrocket, we should be able to make the world much better for everyone.

A transcript of Eric's talk is below, which we have lightly edited for clarity. You can discuss this talk on the EA Forum.

The Talk

This talk is going to be a bit condensed and crowded. I will plow forward at a brisk pace, but this is a marvelous group of people who I trust to keep up wonderfully.

For Paretotopian Goal Alignment, a key concept is Pareto-preferred futures, meaning futures that would be strongly approximately preferred by more or less everyone. If we can have futures like that, that are part of the agenda, that are being seriously discussed, that people are planning for, then perhaps we can get there. Strong goal alignment can make a lot of outcomes happen that would not work in the middle of conflict.

So, when does goal alignment matter. It could matter for changing perceptions. There's the concept of an Overton window, the range of what can be discussed within a given community at a given time, and what can be discussed and taken seriously and regarded as reasonable changes over time. Overton windows also vary by community. The Overton window for discourse in the EA community is different from that in, for example, the public sphere in Country X.

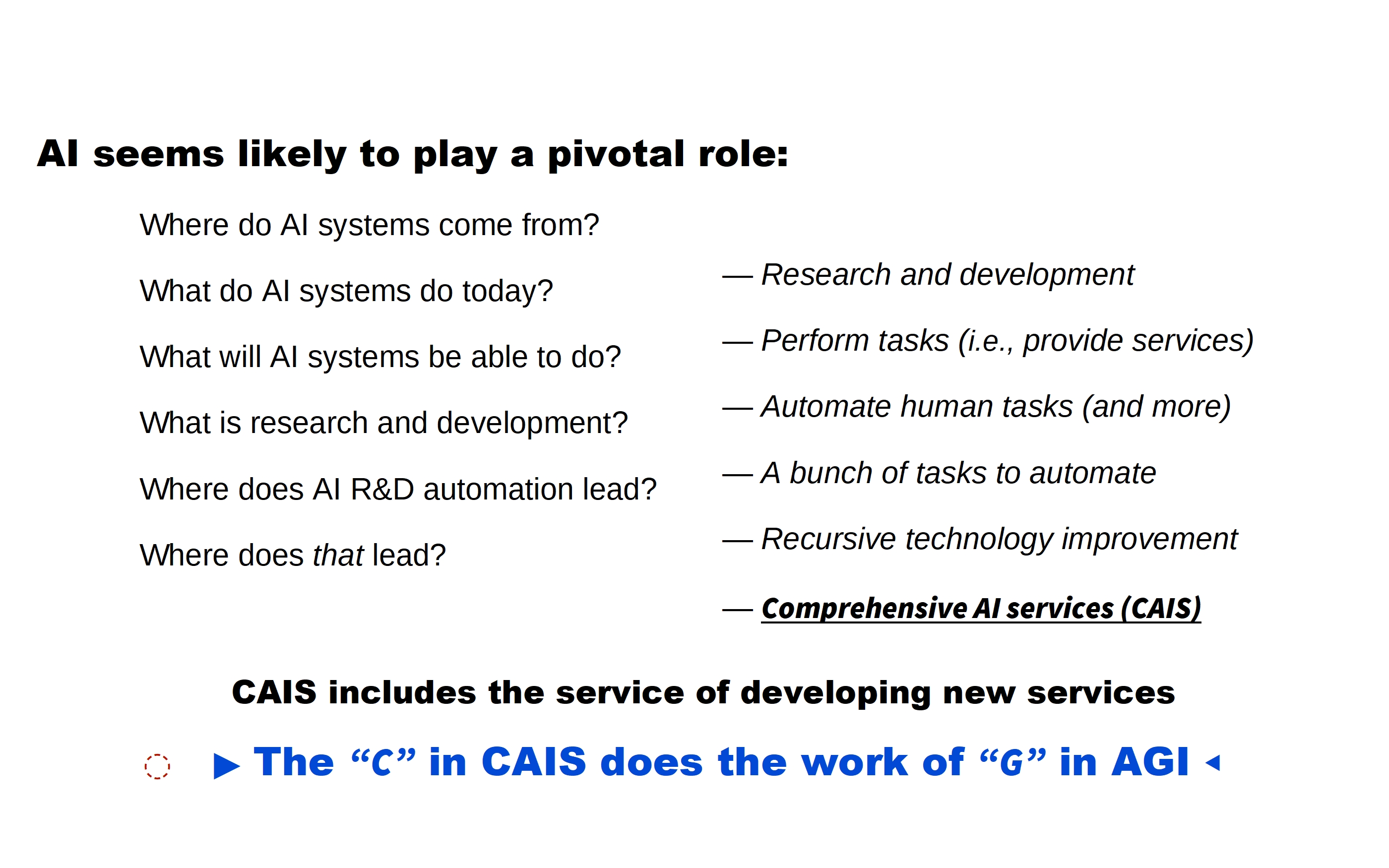

AI seems likely to play a pivotal role. Today we can ask questions we couldn't ask before about AI, back when AI was a very abstract concept. We can ask questions like, "Where do AI systems come from?" Because they're now being developed. They come from research and development processes. What do they do? Broadly speaking, they provide services; they perform tasks in bounded time with bounded resources. What will they be able to do? Well, if you take AI seriously, you expect AI systems to be able to automate more or less any human task. And more than that.

So now we ask, what is research and development? Well, it's a bunch of tasks to automate. Increasingly, we see AI research and development being automated, using software and AI tools. And where that leads is toward what one can call recursive technology improvement. There's a classic view of AI systems building better AI systems. This view has been associated with agents. What we see emerging is recursive technological improvement in association with a technology base. There's an ongoing input of human insights, but human insights are leveraged more and more, and become higher and higher level. Perhaps they also become less and less necessary. So at some point, we have AI development with AI speed.

Where that leads is toward what I describe here as comprehensive AI services. Expanding the range of services, increasing their level toward this asymptotic notion of "comprehensive." What does "comprehensive" mean? Well, it includes the service of developing new services, and that's where generality comes from.

So, I just note that the C in CAIS does the work of G in AGI. So if you ask, "But in the CAIS model, can you do X? Do you need AGI to do X?" Then I say, "What part of 'comprehensive' do you not understand?" I won't be quite that rude, but if you ask, the answer is "Well, it's comprehensive. What is it you want to do? Let's talk about that."

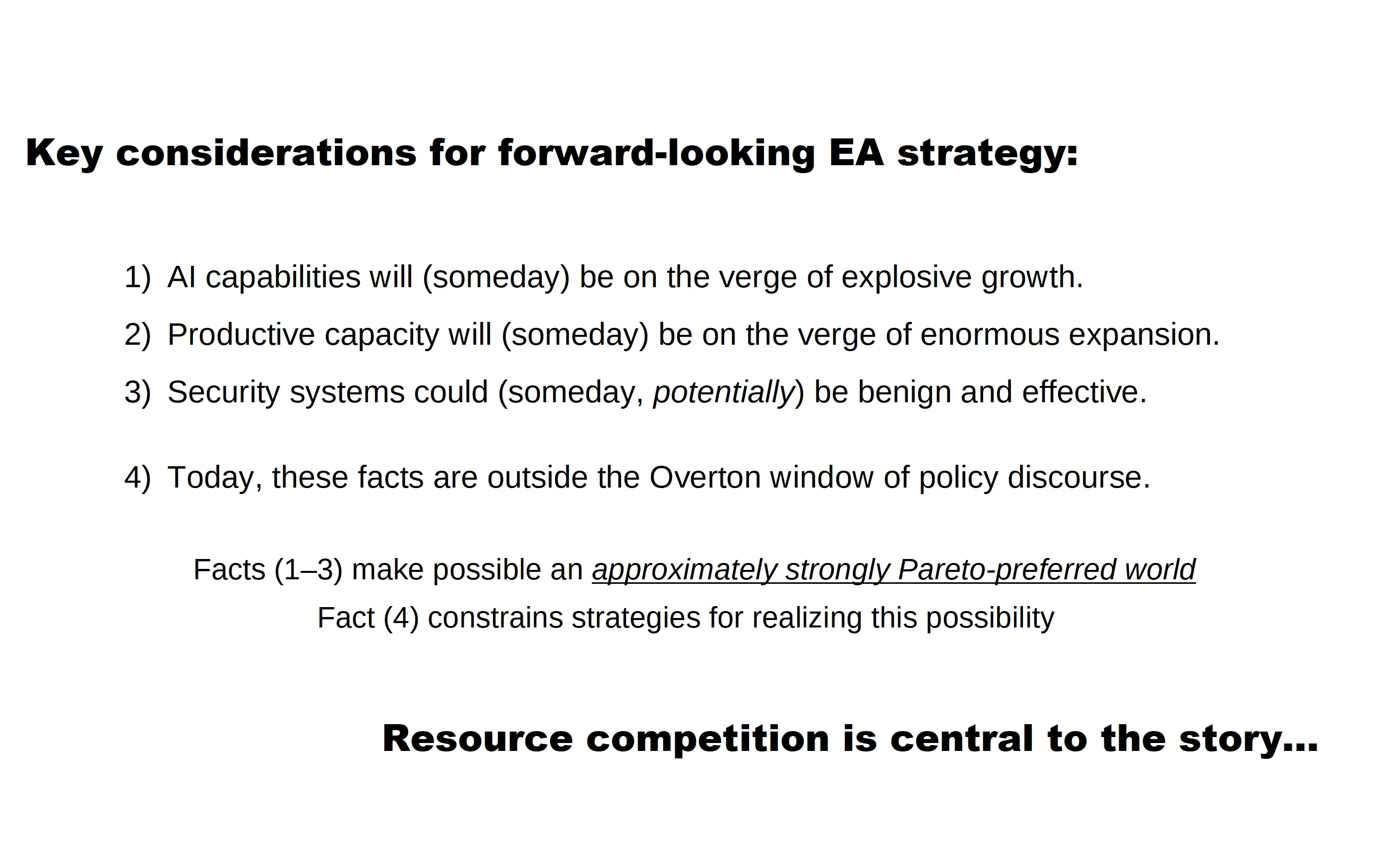

For this talk, I think there are some key considerations for forward-looking EA strategy. This set of considerations is anchored in AI, in an important sense. Someday, I think it's reasonable to expect that AI will be visibly, to a bunch of relevant communities, poised to be on the verge of explosive growth. That it will be sliding into the Overton window of powerful decision-makers.

Not today, but increasingly and very strongly at some point downstream, when big changes are happening before their eyes and more and more experts are saying, "Look at what's happening." As a consequence of that, we will be on the verge of enormous expansion in productive capacity. That's one of the applications of AI: fast, highly effective automation.

Also, this is a harder story to tell, but it follows: if the right groundwork has been laid, we could have systems - security systems, military systems, domestic security systems, et cetera - that are benign in a strong sense, as viewed by almost all parties, and effective with respect to x-risk, military conflict, and so on.

A final key consideration is that these facts are outside the Overton window of policy discourse. One cannot have serious policy discussions based on these assumptions. The other facts make possible an approximately strongly Pareto-preferred world. And the final fact constrains strategies by which we might actually move in that direction and get there.

And that conflict is essential to the latter part of the talk, but first I would like to talk about resource competition, because that's often seen as the "hard question." Resources are bounded at any particular time, and people compete over them. Isn't that a reason why things look like a zero-sum game? And resource competition does not align goals, but instead makes goals oppose each other.

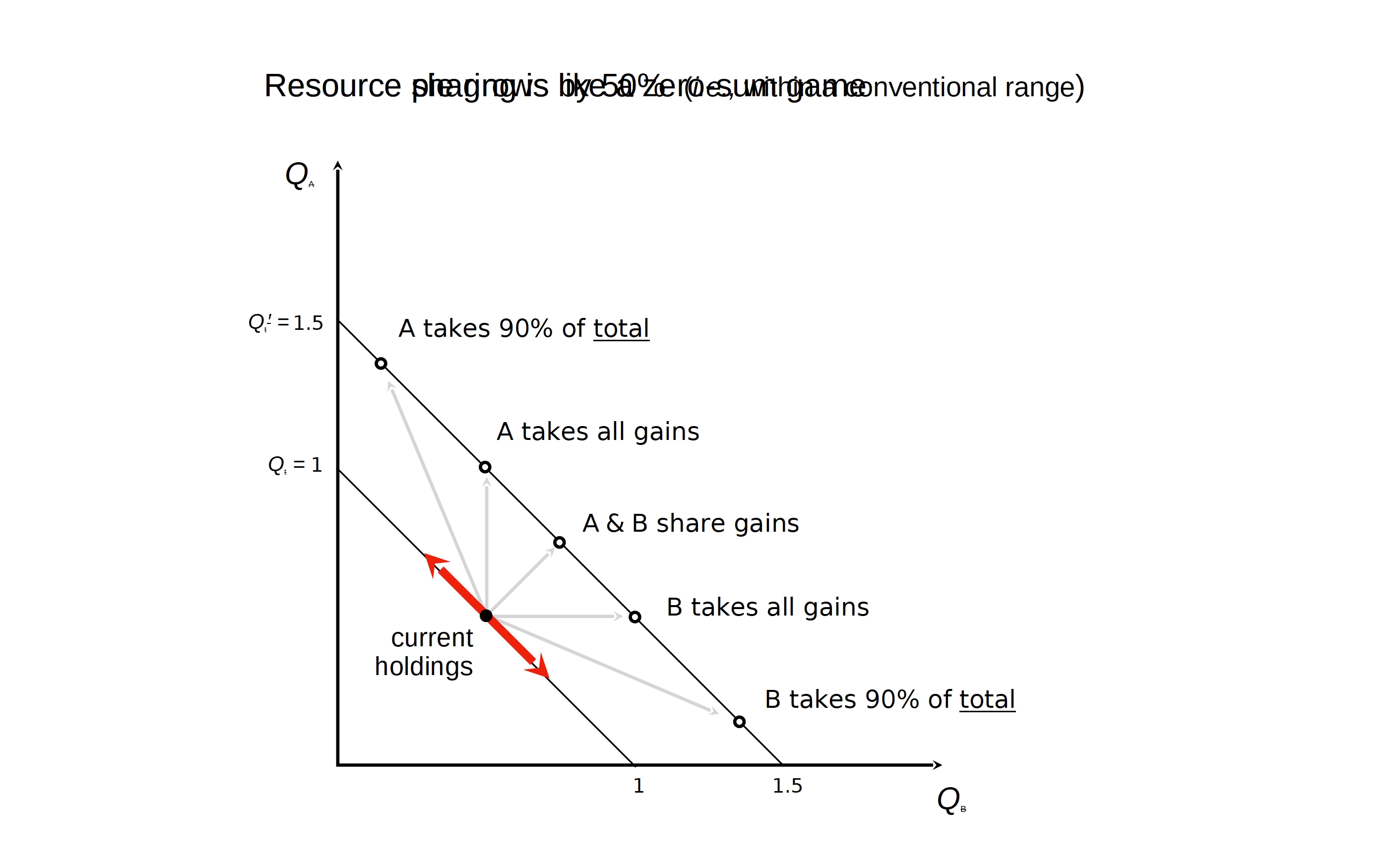

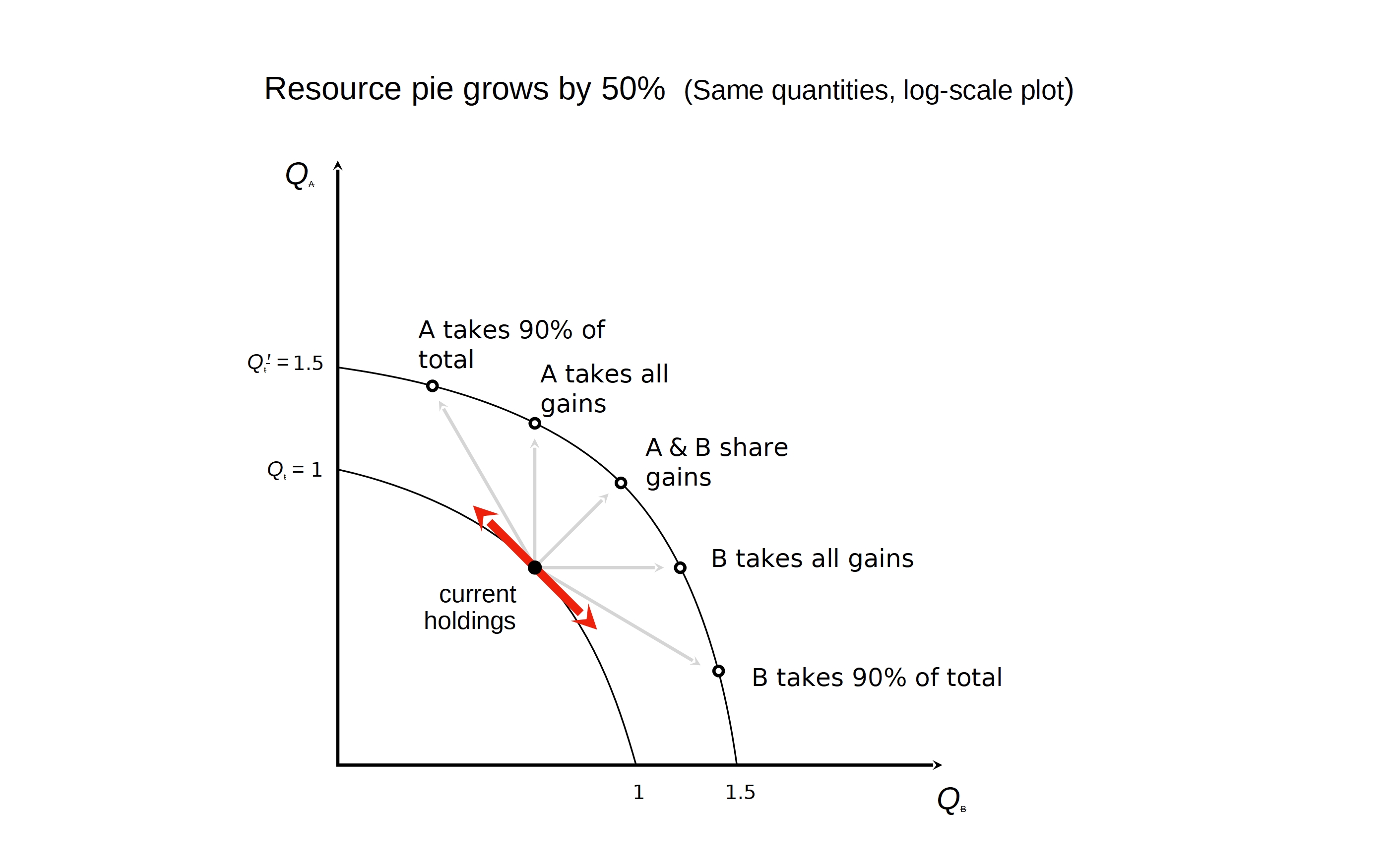

So, here's a graph called "quantity of stuff that party A has," vertically, "quantity of stuff that B has," horizontally. There's a constraint; there's one unit of "stuff," and so the trade-off curve here is a straight line, and changes are on that line, and goals are opposed. Zero-sum game.

In fact, resources increase over time, but the notion of increasing by a moderate number of percent per year is what people have in mind, and the time horizon in which you have a 50% increase is considered very large.

But even with a 50% increase, shown here, if either A or B takes a very large proportion during the shift, like 90%, the other one is significantly worse off than where they started.

Ordinarily, when we're thinking about utility, we don't regard utility as linear in resources, but as something more like the logarithm of resources. We'll adopt that for illustrative purposes here. If we plot the same curves on a log scale, the lines become curved. So there's the same unit constraint. Here's the 50% expansion plotted logarithmically.

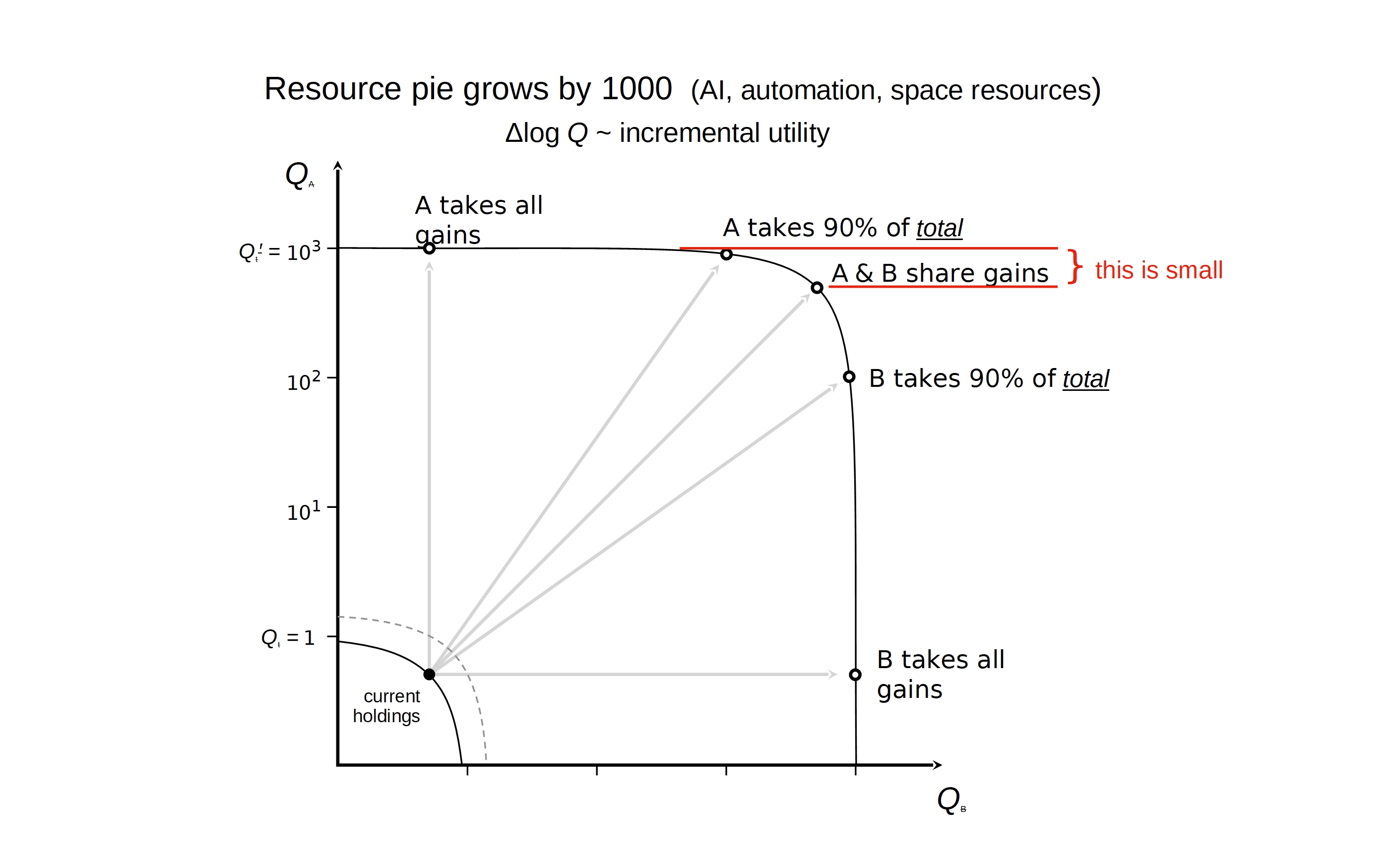

Qualitatively, looks rather similar. Well, the topological relationships are the same, it's just re-plotting the same lines on a log scale. But on a log scale, we can now represent large expansions, and have the geometry reflect utility in a direct visual sense. So there's the same diagram, with current holdings and 50% expansion. And here's what a thousandfold expansion looks like.

Taking all the gains and taking 90% of the total have now switched position. Someone could actually take a large share of resources and everyone would still be way ahead. What matters is that there be some reasonable division of gains. That's a different situation than the 50% increase, where one person taking the vast majority was actively bad for the other.

The key point here is that the difference between taking everything versus having a reasonable share is not very large, in terms of utility. So it's a very different situation than the standard zero-sum game over resources. The reason for this is that we're looking forward to a decision time horizon that spans this large change, which is historically not what we have seen.

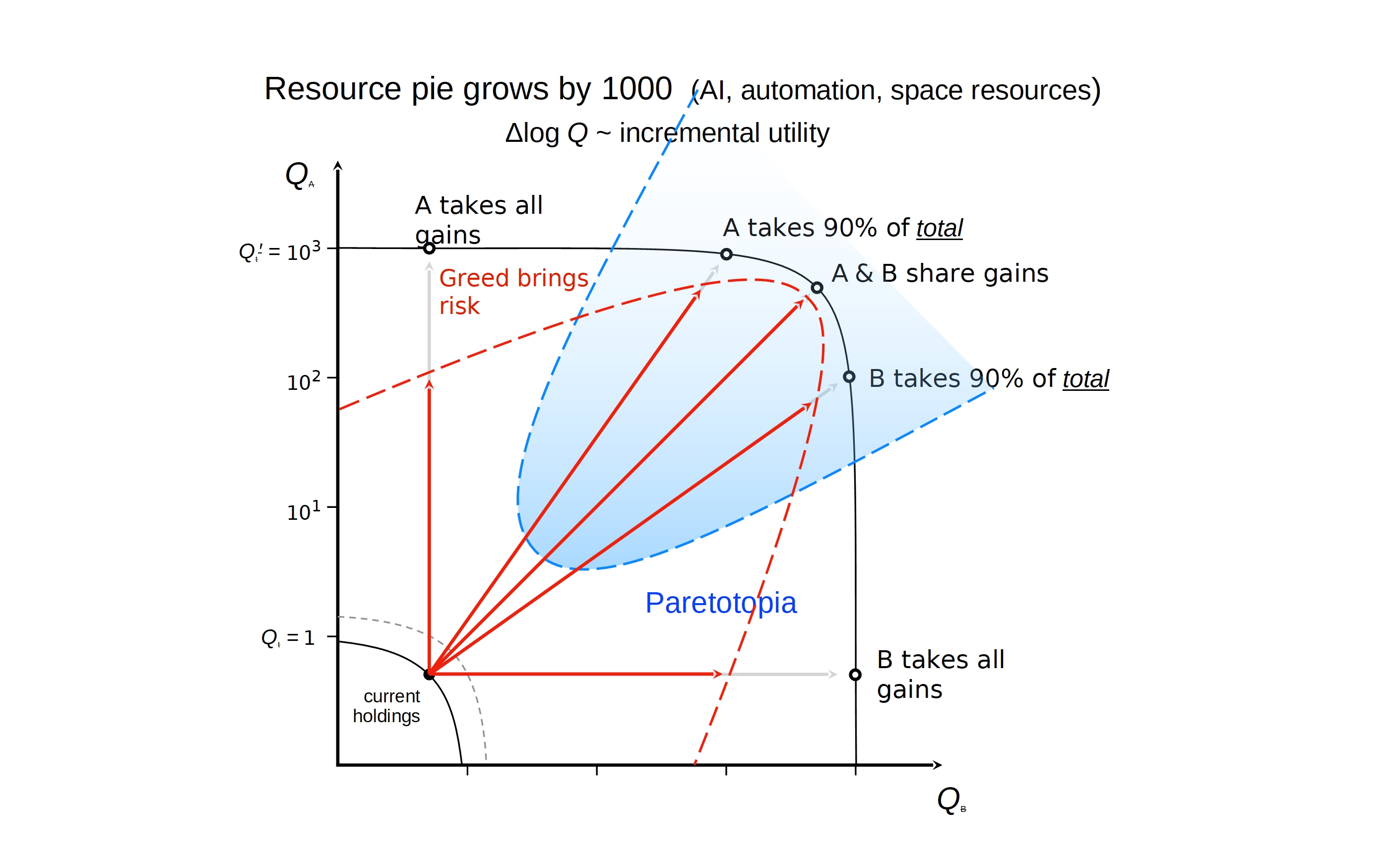

So, let's consider the case for when some party tries to take everything, or tries to take 90%. How far do you get? Well, greed brings risk. This is going to create conflict that is not created by attempting to do that. So the argument here is that not only is there a small increment of gain if you succeed, but, allowing for risk, the gains from attempting to grab everything are negative. Risk-adjusted utility is bad. Your optimum is in fact to aim for some outcome that looks at least reasonably fair to all of the other parties who are in this game, in this process of mutually adjusting policies.

And, so, this region, labeled "Paretotopia", this is a region of outcomes (just looking at resources, although there are many other considerations) in which all parties see very large gains. So, that's a different kind of future to aim at. It's a strongly goal-aligning future, if one can make various other considerations work. The problem is, of course, that this is not inside the window of discussion that one can have in the serious world today.

The first thing to consider is what one can do with resources plus strong AI. It could eliminate poverty while preserving relative wealth. The billionaires would remain on top, and build starships. The global poor remain on the bottom. They only have orbital spacecraft. And I'm serious about that, if you have good productive capability. They expand total wealth while rolling back environmental harms. That's something one can work through, just start looking at the engineering and what one can do with expanded productive capabilities.

A more challenging task is preserving relative status positions while also mitigating oppression. Why do we object to others having a whole lot of resources and security? Because those tend to be used at our expense. But one can describe situations in which oppression is mitigated in a stable way.

Structure transparency is a concept I will not delve into here, but is related to being able to have inherently defensive systems that circumvent the security dilemma, "security dilemma" being the pattern where two parties develop "defensive" weapons that seem aggressive to each other, and so you have an arms race. But if one were able to build truly effective, genuinely defensive systems, it would provide an exit door from that arms race process.

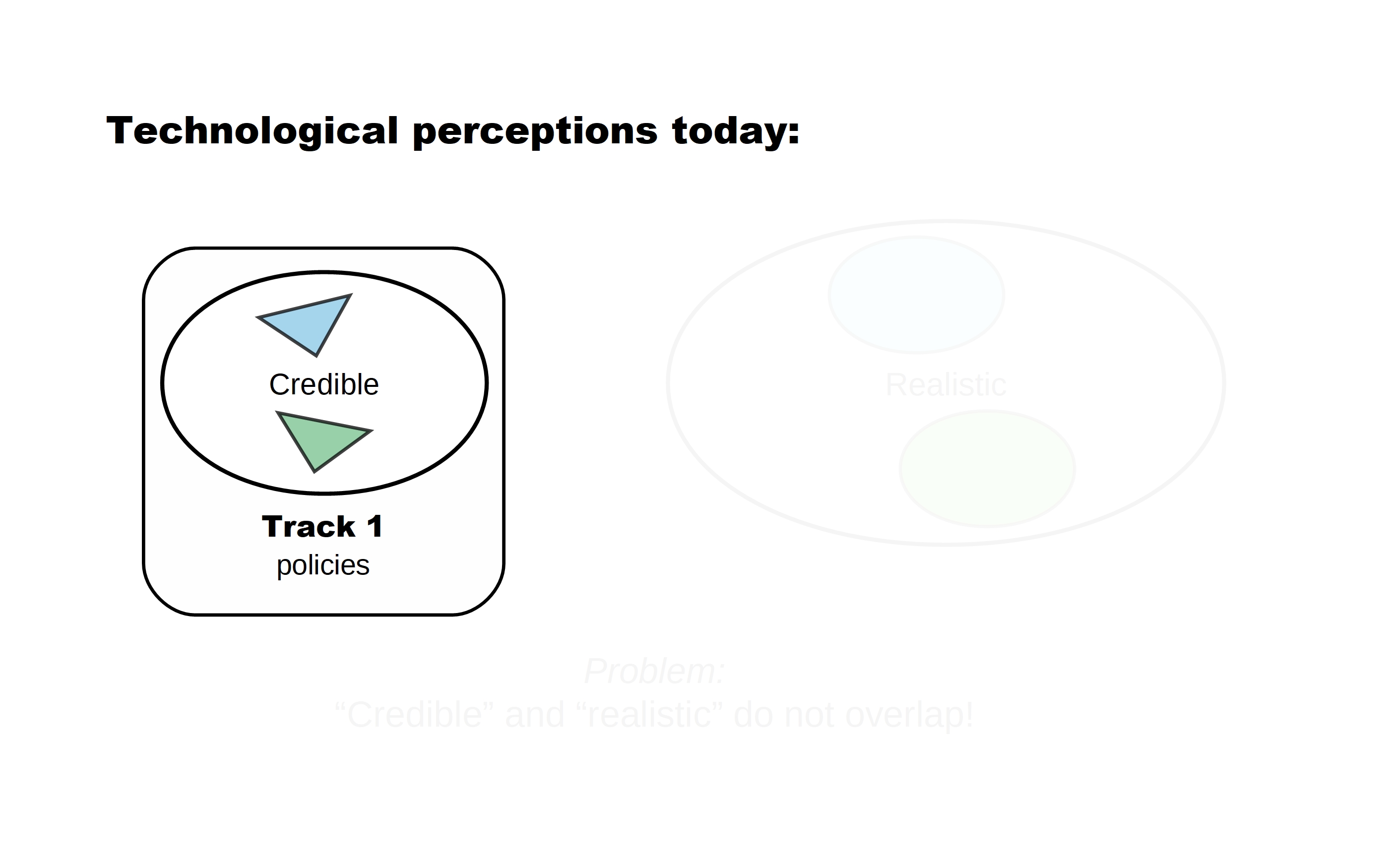

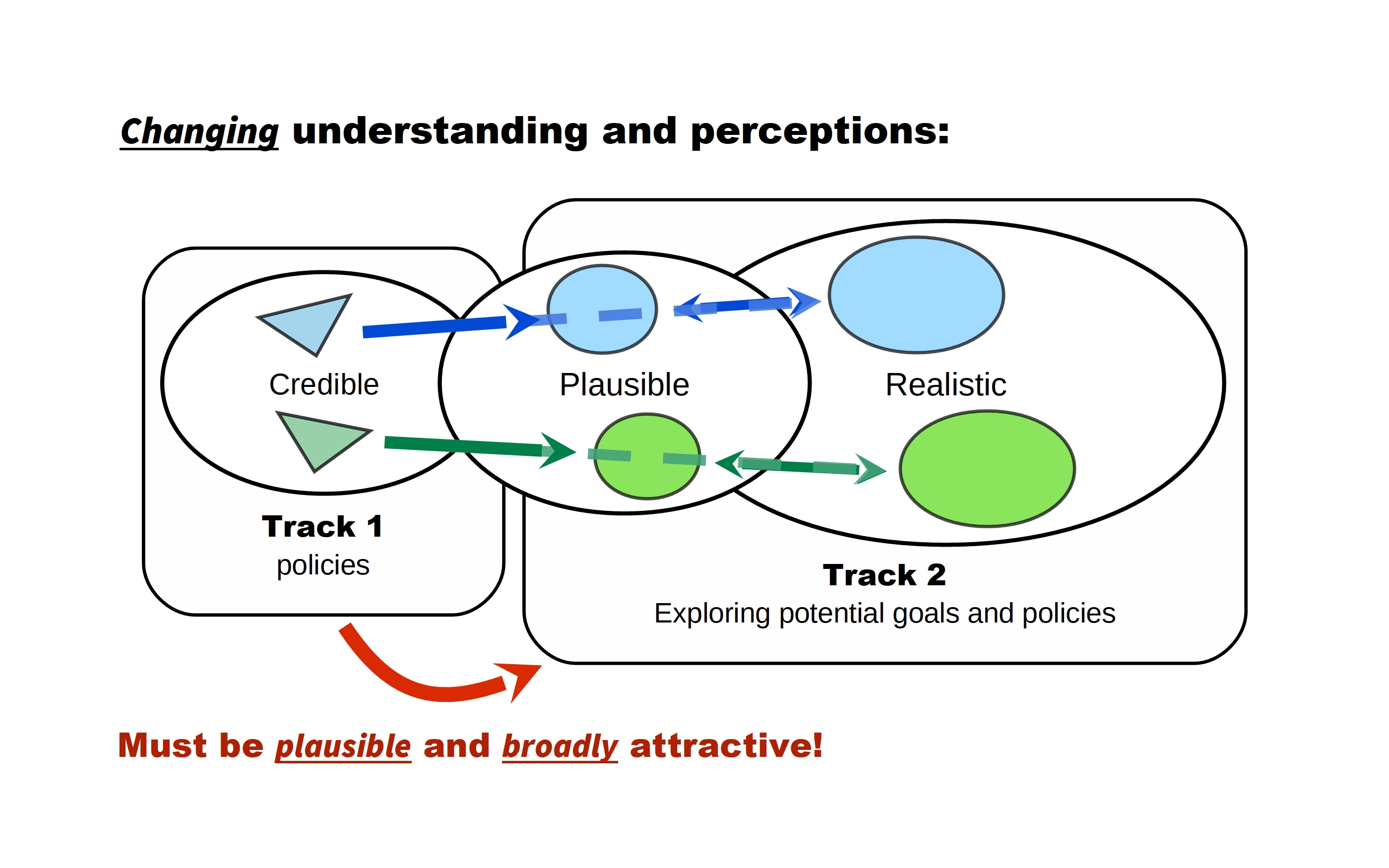

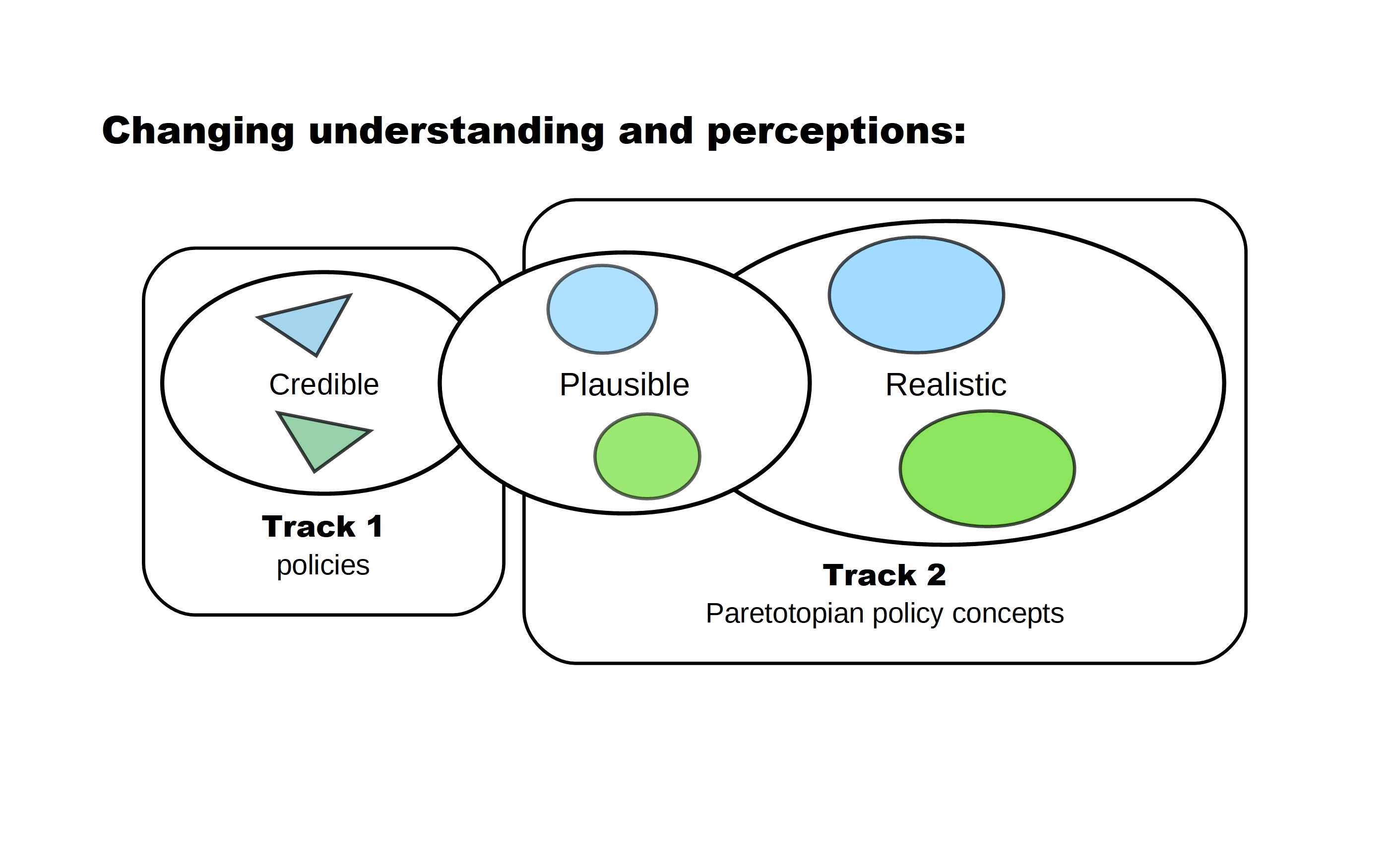

Again, these opportunities are outside the Overton window of current policy discourse. So, where are we today? Well, for technological perceptions, on the one hand we have "credible technologies," and on the other we have "realistic technologies," given what engineering and physics tell us is possible. The problem is that these sets do not overlap. "Credible" and "realistic" are disjoint sets. It's a little hard to plan for the future and get people aligned toward the future in that situation. So, that's a problem. How can one attempt to address it? Well, first we note that at present we have what are called "track one policies," or "business-as-usual policies." What is realistic is not even in the sphere of what is discussed.

Now, I would argue that we, in this community, are in a position to discuss realistic possibilities more. We are, in fact, taking advanced AI seriously. People also take seriously the concept of the "cosmic endowment." So, we're willing to look at this. But how can we make progress in bridging between the world of what is credible, in "track one," and what's realistic?

I think, by finding technologies that are plausible, that are within the Overton window in the sense that discussing contingencies and possible futures like that is considered reasonable. The concepts are not exotic, they're simply beyond what we're familiar with, maybe in directions that people are starting to expect because of AI. And so if this plausible range of technologies corresponds to realistic technologies, the same kinds of opportunities, the same kinds of risks, therefore the same kinds of policies, and also corresponds to what is within the sphere of discourse today... like expanding automation, high production... well, that's known to be a problem and an opportunity today. And so on.

Then, perhaps, one can have a discussion that amounts to what's called "track two," where we have a community that is discussing exploring potential goals and policies, with an eye on what's realistic. Explicit discussion of policies that are both in the "plausible" range and the "realistic" range. Having the plausible policies, the plausible preconditions, be forward in discussion. So, now you have some toehold in the world of what serious people are willing to consider. And increasingly move these kinds of policies, which will tend to be aligned policies that we're exploring, into the range of contingency planning, for nations, for institutions, where people will say, "Well, we're focusing of course on the real world and what we expect, but if this crazy stuff happens, who knows."

They'll say, "People are thinking AI might be a big deal, you folks are telling us that AI will expand resources, will make possible change in the security environment, and so on. Well, that's nice. You think about that. And if it happens, maybe we'll take your advice. We'll see."

So, in this endeavor, one has to work on assumptions and policies that are both plausible and would, if implemented, be broadly attractive. So, that's a bunch of intellectual work. I'll get into the strategic context next, but I'll spend a couple moments on working within the Overton window of plausibility first.

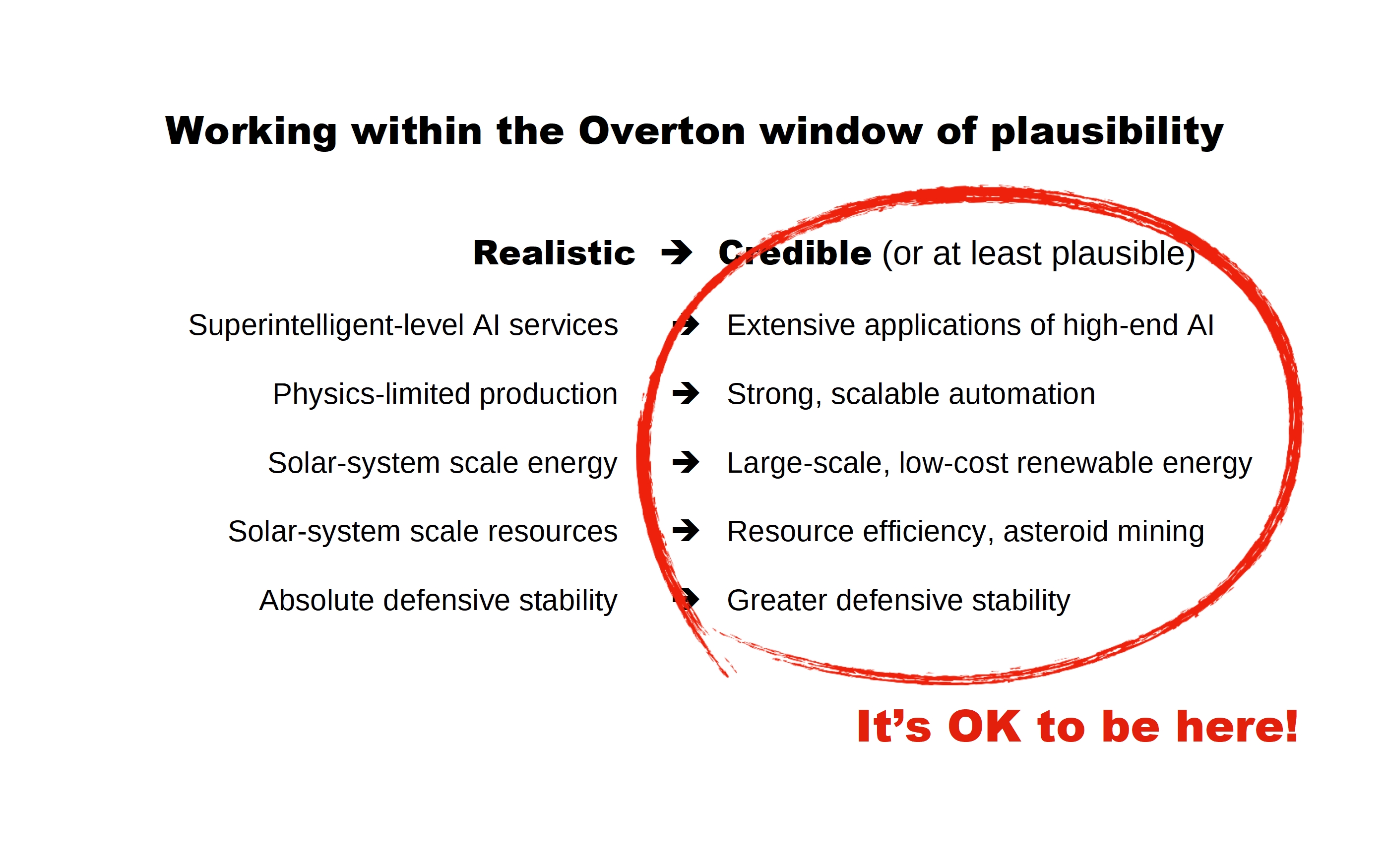

So, realistic: superintelligent-level AI services. Credible: extensive applications of high-end AI. People are talking about that. Physics-limited production. Truly science fiction in quality. Well, a lot of the same issues arise from strong scalable automation, of the sort that people are already worried about in the context of jobs. Solar system scale energy, 10^26 watts. Well, how about breaking constraints on terrestrial energy problems by having really inexpensive solar energy? It can expand power output, decrease environmental footprint, and actually do direct carbon capture, if you have that amount of energy. Solar system scale resources, kind of off the table, but people are beginning to talk about asteroid mining. Resource efficiency, and one can argue that resources are not binding on economic growth in the near term, and that's enough to break out of some of the zero-sum mentality. Absolute defensive stability is realistic but not something that is credible, but moving toward greater defensive stability is.

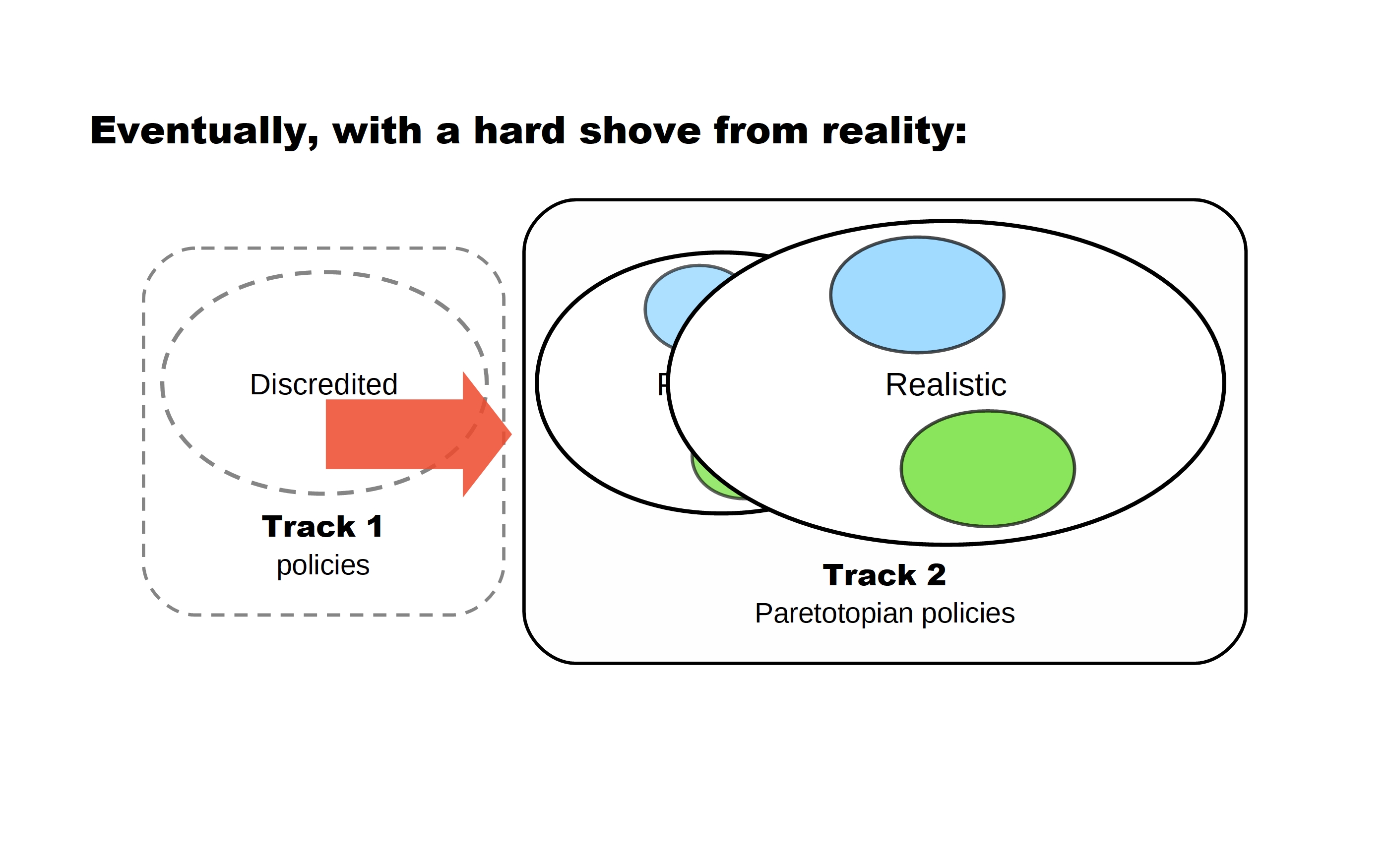

And note, it's okay to be on the right side of this slide. You don't necessarily, here in this room, have to take seriously superintelligent-level AI services, alert systems, scale resources and so on, to be playing the game of working within the range of what is plausible in the more general community, and working through questions that would constitute "Paretotopian goal-aligning policies" in that framework. So the argument is that eventually, reality will give a hard shove. Business-as-usual scenarios, at least the assumptions behind them, will be discredited and, if we've done our work properly, so will the policies that are based on those assumptions. The policies that lead to the idea that maybe we should be fighting over resources in the South China Sea just look absurd, because everyone knows that in a future of great abundance, fighting over something is worthless.

So, if the right intellectual groundwork has been done, then, when there's a hard shove from reality that is toward a future that has Paretotopian potential, there will be a coherent policy picture that is coherent across many different institutions, with everyone knowing that everyone else knows that it would be good to move in this direction. Draft agreements worked out in track two diplomacy, scenario planning that suggests it would be really stupid to pursue business as usual in arms races. If that kind of work is in place, then with a hard shove from reality, we might see a shift. Track one policies are discredited, and so people ask, "What should we do? What do we do? The world is changing."

Well, we could try these new Paretotopian policies. They look good. If you fight over stuff, you probably lose. And if you fight over it, you don't get much if you win, so why not go along with the better option, which has been thought through in some depth and looks attractive?

So that is the basic Paretotopian strategic idea. We look at these great advances, back off to plausible assumptions that can be discussed in that framework, work through interactions with many, many different groups, reflecting diverse concerns that, in many cases, will seem opposed but can be reconciled given greater resources and the ability to make agreements that couldn't be made in the absence of, for example, strong AI implementation abilities. And so, finally, we end up in a different sort of world.

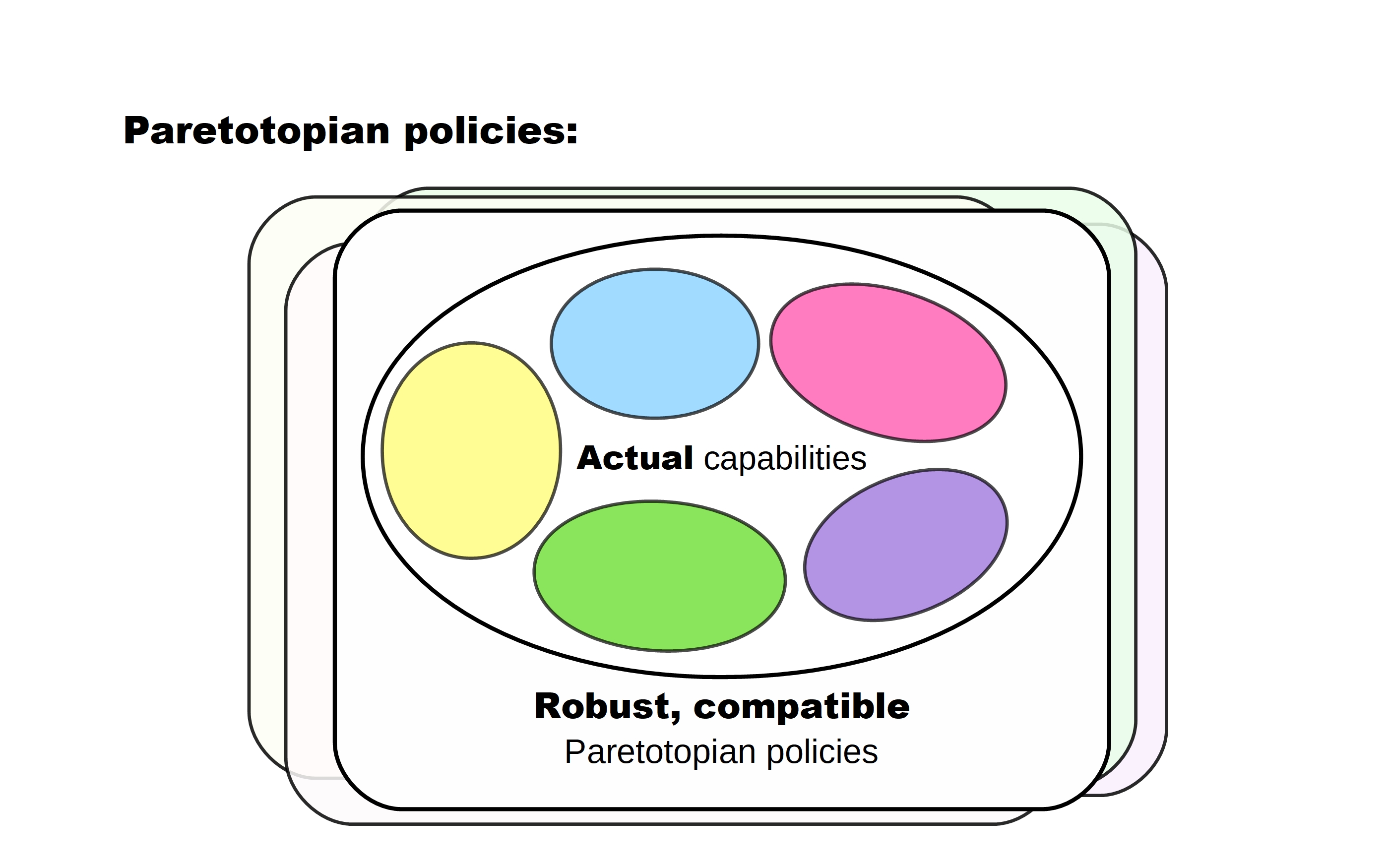

Now, this says "robust." Robust against what? All of the capabilities that are not within the range of discussion or that are simply surprising. "Compatible." Well, Paretotopian policies aren't about having one pattern on the world, it really means many different policies that are compatible in the sense that the outcomes are stable and attractive.

And with that, the task at hand, at least in one of the many directions that the EA community can push, and a set of considerations that I think are useful background and context for many other EA activities, is formulating and pursuing Paretotopian meta-strategies, and the framework for thinking about those strategies. That means understanding realistic and credible capabilities, and then bridging the two. There's a bunch of work on both understanding what's realistic and what is credible, and the relationships between these. There's work on understanding and accommodating diverse concerns. One would like to have policies that seem institutionally acceptable to the U.S. military, and the Communist Party of China, and to billionaires, and also make the rural poor well-off, and so on, and have those be compatible goals. And to really understand the concerns of those communities, in their own conceptual and idiomatic languages. That's a key direction to pursue. And that means deepening and expanding the circle of discourse that I'm outlining.

And so, this is a lot of hard intellectual work and, downstream, increasing organizational work. I think that pretty much everything one might want to pursue in the world that is good fits broadly within this framework, and can perhaps be better oriented with some attention to this meta-strategic framework for thinking about goal alignment. And so, thank you.