Contents

- Introduction

- What are some examples of effective altruism in practice?

- What principles unite effective altruism?

- How can you take action?

Introduction

Effective altruism is a project that aims to find the best ways to help others, and put them into practice.

It’s both a research field, which aims to identify the world’s most pressing problems and the best solutions to them, and a practical community that aims to use those findings to do good.

This project matters because, while many attempts to do good fail, some are enormously effective. For instance, some charities help 100 or even 1,000 times as many people as others, when given the same amount of resources.

This means that by thinking carefully about the best ways to help, we can do far more to tackle the world’s biggest problems.

Effective altruism was formalized by scholars at Oxford University, but has now spread around the world, and is being applied by tens of thousands of people in more than 70 countries.1

People inspired by effective altruism have worked on projects that range from funding the distribution of 200 million malaria nets, to academic research on the future of AI, to campaigning for policies to prevent the next pandemic.

They’re not united by any particular solution to the world’s problems, but by a way of thinking. They try to find unusually good ways of helping, so that a given amount of effort goes an unusually long way. Below are some examples of what they've done so far, followed by the values that unite them.

What are some examples of effective altruism in practice?

Preventing the next pandemic

Why this issue?

People in effective altruism typically try to identify issues that are big in scale, tractable, and unfairly neglected.2 The aim is to find the biggest gaps in current efforts, in order to find where an additional person can have the greatest impact. One issue that seems to match those criteria is preventing pandemics.

Researchers in effective altruism argued as early as 2014 that, given the history of near-misses, there was a good chance that a large pandemic would happen in our lifetimes.

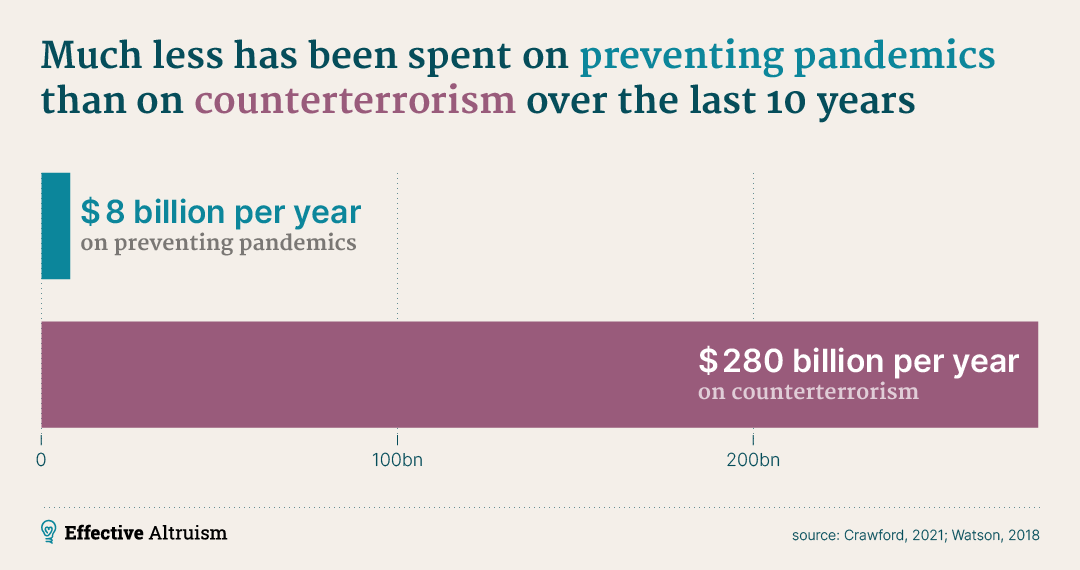

But preparing for the next pandemic was, and remains, hugely underfunded compared to other global issues. For instance, the US invests around $8bn per year preventing pandemics, compared to around $280bn per year spent on counterterrorism over the last decade.3

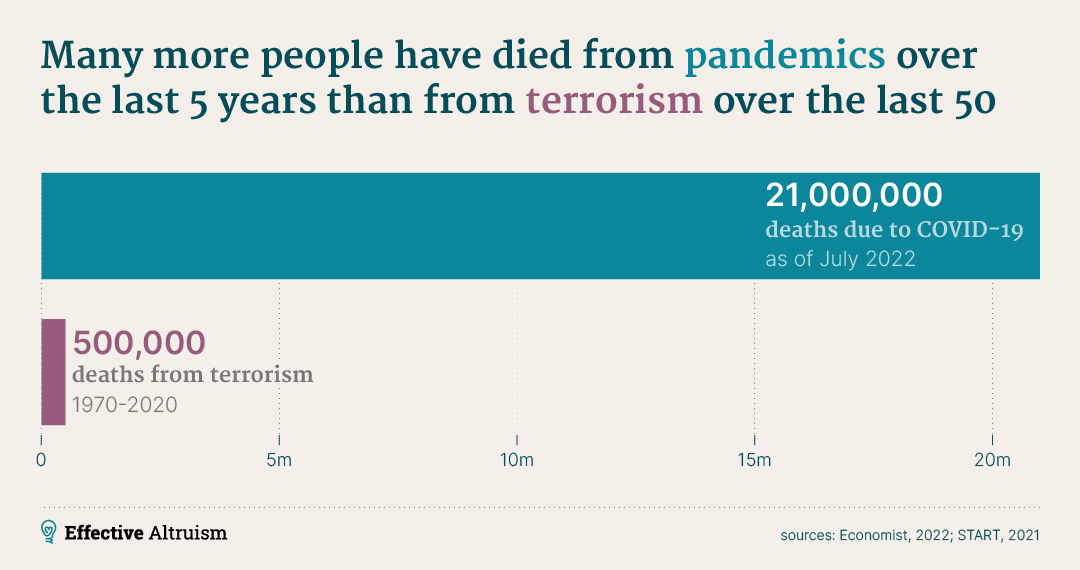

Preventing terror attacks is certainly important. But the scale of the issue seems smaller. For instance, just to focus on the number of deaths, in the last 50 years, around 500,000 people have been killed by terrorism. But over 21 million people were killed by COVID-19 alone4 – or consider the 40 million killed by HIV/AIDS.5

Not to mention, a future pandemic could easily be much worse than COVID-19: there’s nothing to rule out a disease that’s more infectious than the Omicron variant, but that’s as deadly as smallpox. (See more on the comparison in footnote 4.)

In effective altruism, once a big and neglected problem has been identified, the community then looks for solutions that have a chance of making a big contribution to solving the problem, and are neglected by others working on that issue, which brings us to...

Some examples of what’s been done

In 2016 Open Philanthropy – a foundation inspired by effective altruism – became the largest funder of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, which is one of the few groups doing research to identify better policy responses to pandemics, and was an important group in the response to COVID-19.6

When COVID-19 broke out, members of the community founded 1DaySooner, a non-profit that advocates for human challenge trials. In this type of vaccine trial, healthy volunteers are deliberately infected with the disease, enabling near-instant testing of the vaccine. As one of the only advocates for this intervention, 1DaySooner has signed up over 30,000 volunteers,7 and played an important role in starting the world’s first COVID-19 human challenge trial. This model can be repeated when we face the next pandemic.

Members of the effective altruism community helped to create the Apollo Programme for Biodefense, a multibillion dollar policy proposal designed to prevent the next pandemic.

Providing basic medical supplies in poor countries

Why this issue?

It’s common to say that charity begins at home, but in effective altruism, charity begins where we can help the most. And this often means focusing on the people who are most neglected by the current system – which is often those who are more distant from us.

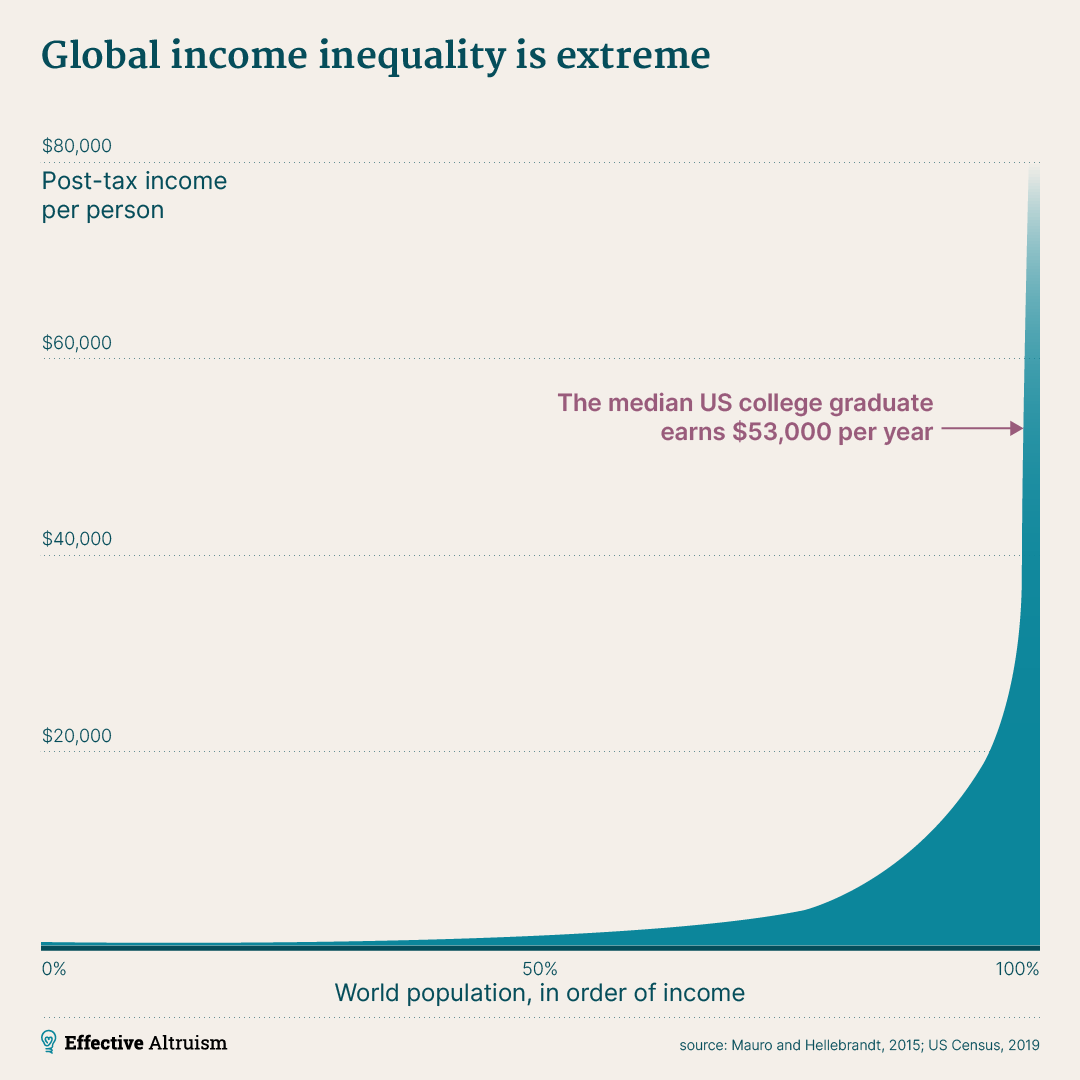

Over 700 million people live on less than $1.90 per day.8

In contrast, an American living near the poverty line lives on 20 times as much, and the average American college graduate lives on about 107 times as much. This places them in the top 1.3% of income, globally speaking.9 (These amounts are already adjusted for the fact that money goes further in poor countries.)

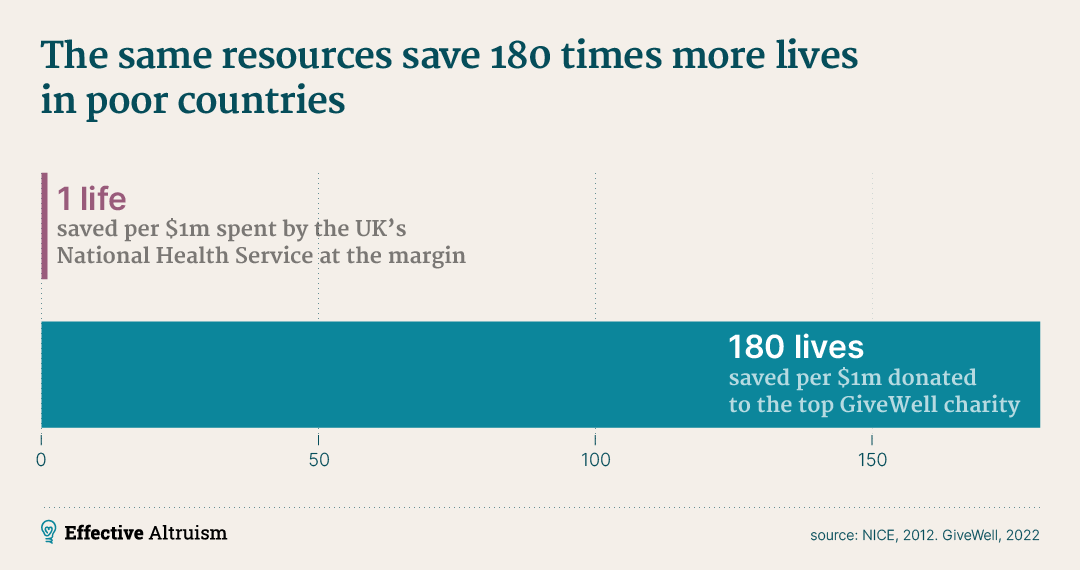

Global inequality is extreme. Because of this, transferring resources to the very poorest people in the world can do a huge amount of good. In richer countries like the US and UK, governments are typically willing to spend over $1 million to save a life.10 This is well worth doing, but in the world’s poorest countries, the cost of saving a life is far lower.

GiveWell is an organization that does in-depth research to find the most evidence-backed and cost-effective health and development projects. It discovered that while many aid interventions don’t work, some, like providing insecticide-treated bednets, can save a child’s life for about $5,500 on average. That's 180 times less.11

These basic medical interventions are so cheap and effective that even the most prominent aid sceptics agree they’re worthwhile.

Some examples of what’s been done

Over 110,000 individual donors have used GiveWell’s research to contribute more than $1 billion to its recommended charities, supporting organisations like the Against Malaria Foundation, which has distributed over 200 million insecticide-treated bednets. Collectively these efforts are estimated to have saved 159,000 lives.12

In addition to charity, it’s possible to help the world’s poorest people through business. Wave is a technology company founded by members of the effective altruism community, which allows people to transfer money to several African countries faster and several times more cheaply than existing services. It’s especially helpful for migrants sending money home to their families, and has been used by over 800,000 people in countries like Kenya, Uganda and Senegal. In Senegal alone, Wave has saved its users hundreds of millions of dollars in transfer fees – around 1% of the country’s GDP.13

Helping to create the field of AI alignment research

Why this issue?

People in effective altruism often end up focusing on issues that seem counterintuitive, obscure or exaggerated. But this is because it’s more impactful to work on the issues that are neglected by others (all else equal), and these issues are (almost by definition) going to be unconventional ones. One example is the AI alignment problem.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is progressing rapidly. The leading AI systems are now able to engage in limited conversation, solve college-level maths problems, explain jokes, generate extremely realistic images from text, and do basic coding.14 None of this was possible just ten years ago.

The ultimate goal of the leading AI labs is to develop AI that is as good as, or better than, human beings on all tasks. It’s extremely hard to predict the future of technology, but various arguments and expert surveys suggest that this achievement is more likely than not this century. And according to standard economic models, once general AI can perform at human level, technological progress could dramatically accelerate.

The result would be an enormous transformation, perhaps of a significance similar to or greater than the industrial revolution in the 1800s. If handled well, this transformation could bring about abundance and prosperity for everyone. If handled poorly, it could result in an extreme concentration of power in the hands of a tiny elite.

In the worst case, we could lose control of the AI systems themselves. Unable to govern beings with capabilities far greater than our own, we would find ourselves with as little control over our future as chimpanzees have control over theirs.

This means this issue could not only have a dramatic impact on the present generation, but also on all future generations. This makes it especially pressing from a “longtermist” perspective, a school of thinking which holds that improving the long-term future is a key moral priority of our time.

How to ensure AI systems continue to further human values, even as they become equal (or superior) to humans in their capabilities, is called the AI alignment problem, and solving it requires advances in computer science.

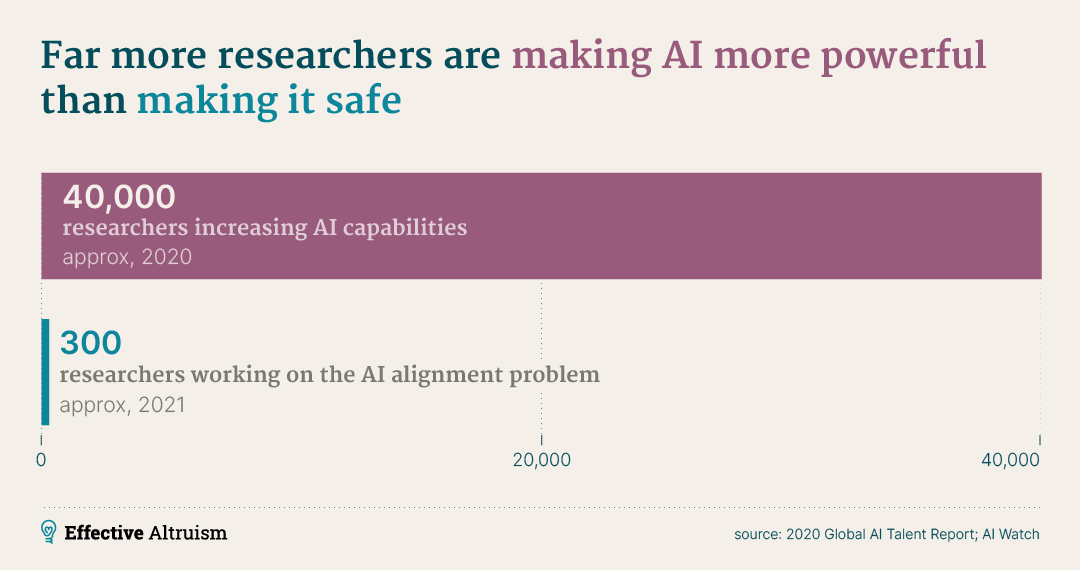

Despite its potentially historical importance, only a couple of hundred researchers work on this problem, compared to tens of thousands working to make AI systems more powerful.15

It’s hard to sum up the case for the issue in a few paragraphs, so if you’d like to explore more, we’d recommend starting here, here and here.

Some examples of what’s been done

One priority is to simply tell more people about the issue. The book Superintelligence was published in 2014, making the case for the importance of AI alignment, and became a New York Times best-seller.

Another priority is to build a research field focused on this problem. For instance, AI pioneer Stuart Russell, and others inspired by effective altruism, founded The Center for Human-Compatible AI at UC Berkeley. This research institute aims to develop a new paradigm of AI development, in which the act of furthering human values is central.

Others have helped to start teams focused on AI alignment at major AI labs such as DeepMind and OpenAI, and outline research agendas for AI alignment, in works such as Concrete Problems in AI Safety.

Ending factory farming

Why this issue?

People in effective altruism try to extend their circle of concern – not only to those living in distant countries or future generations, but also to non-human animals.

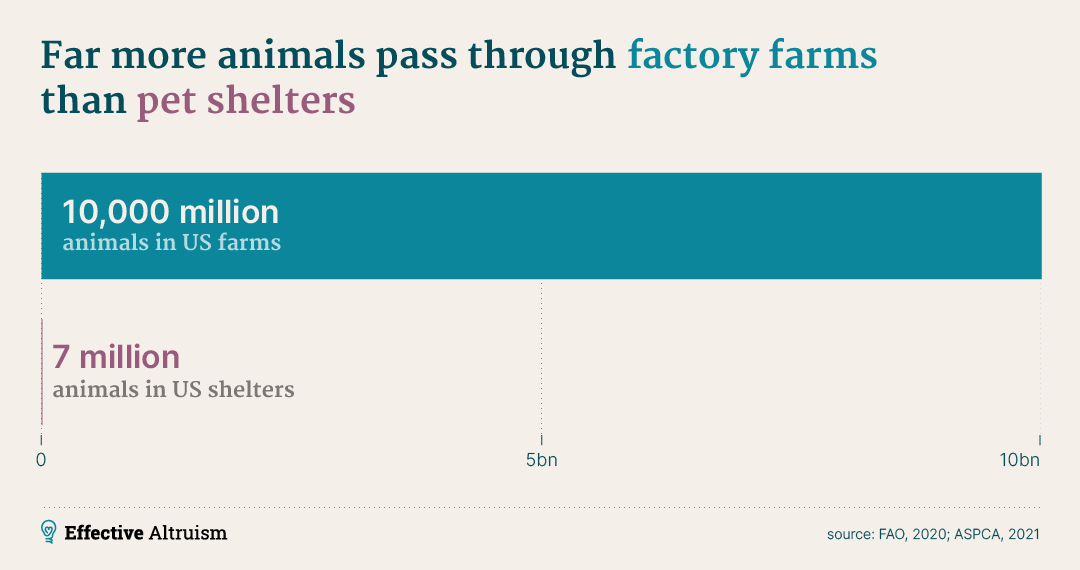

Nearly 10 billion animals live and die in factory farms in the US every year16 – often unable to physically turn around their entire lives, or castrated without anaesthetic.

Lots of people agree we shouldn’t make animals suffer needlessly, but most of this attention goes towards pet shelters. In the US, about 1,400 times more animals pass through factory farms than pet shelters.17

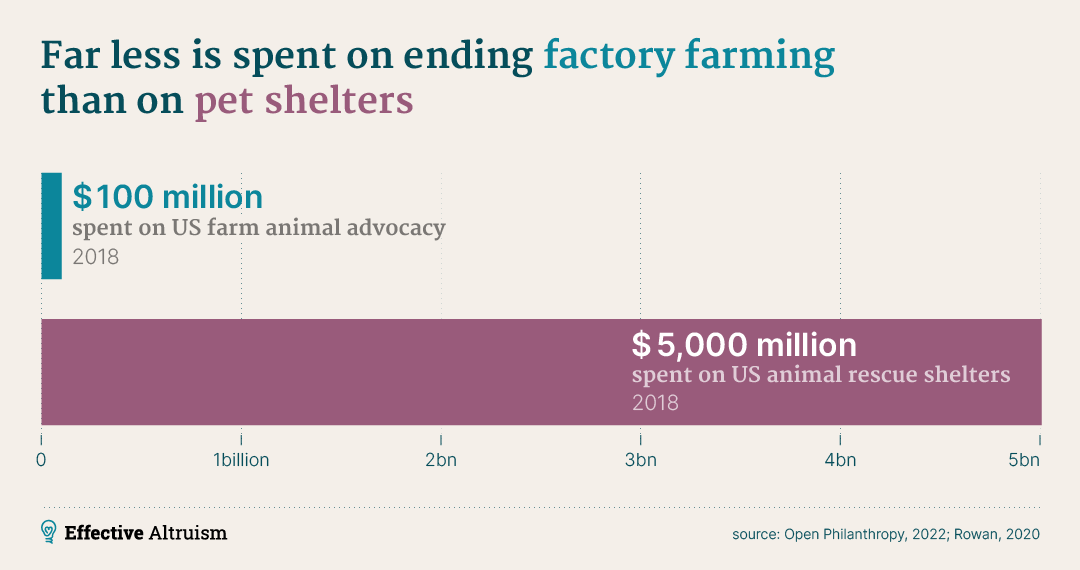

Despite this, pet shelters receive around $5 billion per year in the US, compared to only $97 million on advocacy to end factory farming.18

Some examples of what’s been done

One strategy is advocacy. The Open Wing Alliance, which received significant funding from funders inspired by effective altruism, developed a campaign to encourage large companies to commit to stop buying eggs from caged chickens. To date, they have won over 2,200 commitments, and as a result over 100 million birds have been spared from cages.19

Another strategy is to create alternative proteins, which if made cheaper and tastier than factory farmed meat, could make demand disappear, ending factory farming. The Good Food Institute is working to kick-start this industry, helping to create companies like Dao Foods in China and Good Catch in the US, encouraging big business to enter the industry (including JBS, the world’s largest meat company) and securing tens of millions of dollars of government support.20

Open Philanthropy was an early investor in Impossible Foods, which created the Impossible Burger – an entirely vegan burger that tastes much more like meat, and is now sold in Burger King.

Improving decision-making

Why this issue?

People who want to do good often prefer to directly tackle problems, since it’s more motivating to see the tangible effects of their actions. But what matters is that the world gets better, not that you do it with your own two hands. So people applying effective altruism often try to help indirectly, by empowering others.

One example of this is by improving decision-making. Namely: if key actors — such as politicians, private and third sector leaders, or grantmakers at funding bodies — were generally better at making decisions, society would be in a better position to deal with a whole range of future global problems, whatever they turn out to be.

So, if we can find new, neglected ways to improve the decision-making of important actors, that could be a route to having a big impact. And it seems like there are some promising solutions that could achieve this.

Some examples of what’s been done

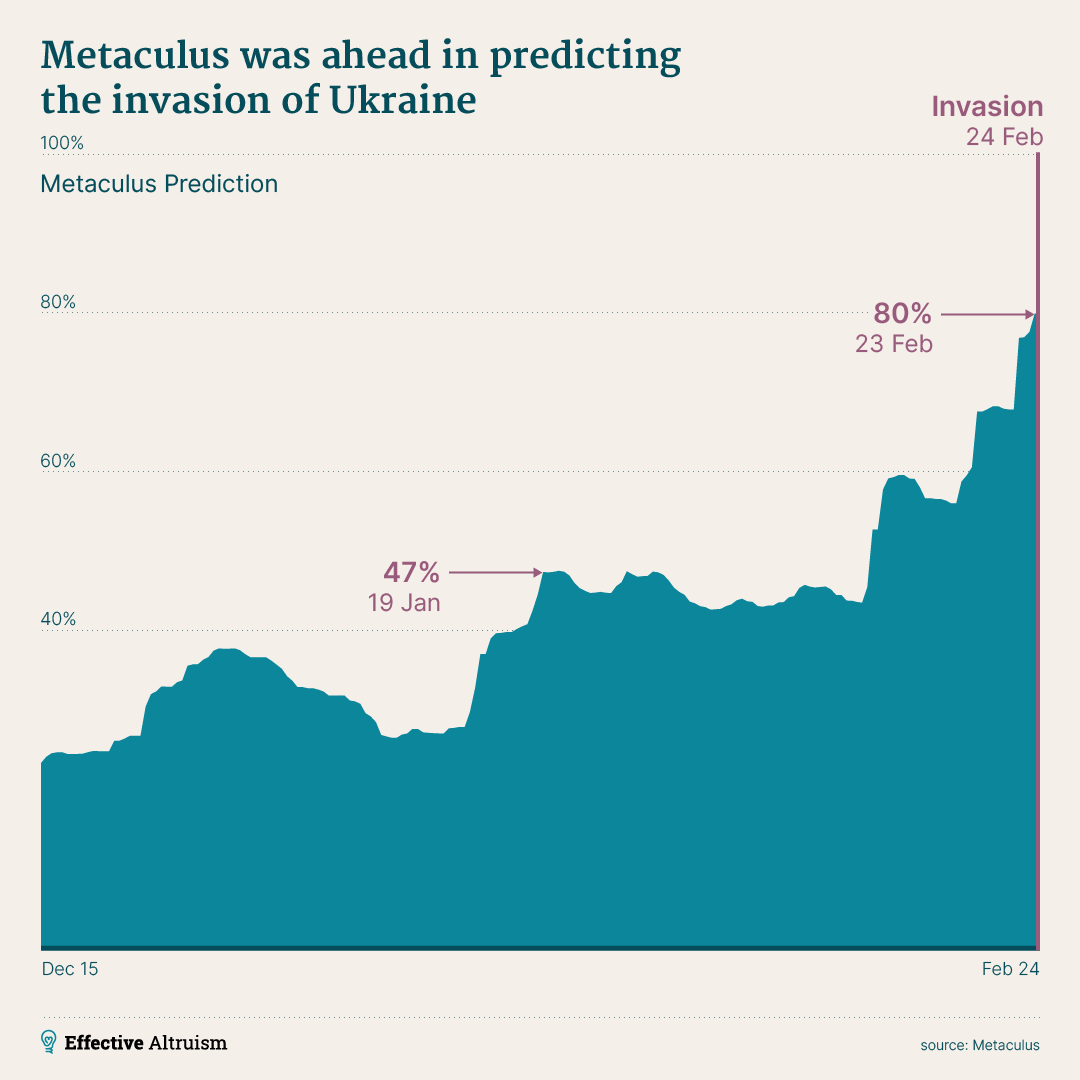

Many global problems are exacerbated by a lack of trustworthy information. Metaculus is a forecasting technology platform that identifies important questions (such as the chance of Russia invading Ukraine), aggregates forecasts made by hundreds of forecasters, and weighs them by their past accuracy. Metaculus gave a probability of a Russian invasion of Ukraine of 47% by mid January 2022, and 80% shortly before the invasion on the 24th of February21 – a time when many pundits, journalists and experts were saying it definitely wouldn’t happen.

The Global Priorities Institute at the University of Oxford does foundational research at the intersection of philosophy and economics into how key decision-makers can identify the world’s most pressing problems. It has helped to create a new academic field of global priorities research, creating a research agenda, publishing tens of papers, and helping to inspire relevant research at Harvard, NYU, UT Austin, Yale, Princeton and elsewhere.

What principles unite effective altruism?

Effective altruism isn't defined by the projects above, and what it focuses on could easily change. What defines effective altruism are the principles that underpin its search for the best ways of helping others:

-

Scope sensitivity: We're committed to prioritizing actions that benefit more lives over actions that benefit fewer. The difference between saving a billion lives and saving ten isn't just a matter of degree — it's a fundamental difference in scale that should guide decisions about where to focus our efforts.

-

Impartiality: We aim to assist those who need it most without giving extra weight to people who are similar to us or geographically close. This approach often points us toward supporting people in developing countries, non-human animals, and future generations whose needs might otherwise be overlooked.

-

Scout mindset: We can help others more effectively when we work together to think clearly and orient toward truth, rather than defending our existing ideas. Since humans naturally struggle with biases and motivated reasoning, we try to cultivate intellectual humility by testing our beliefs and updating our views when presented with contrary evidence.

-

Recognition of tradeoffs: Because our time and money are limited, every choice to support one cause means not supporting another. We acknowledge these opportunity costs and try to make deliberate decisions about how to allocate our resources, recognizing that saying yes to one intervention often means saying no to others that might also do good.

These principles are not absolutes, and could change, but we think they’re important and undervalued by society at large. Anyone applying these principles in trying to find better ways to help others is participating in effective altruism. This is true no matter how much time or money they want to give, or which issue they choose to focus on.

It’s often possible to achieve more by working together, and doing this effectively requires high standards of honesty, integrity, and compassion. Effective altruism does not mean supporting ‘ends justify the means’ reasoning, but rather is about being a good citizen, while ambitiously working toward a better world.

Effective altruism can be compared to the scientific method. Science is the use of evidence and reason in search of truth – even if the results are unintuitive or run counter to tradition. Effective altruism is the use of evidence and reason in search of the best ways of doing good.

The scientific method is based on simple ideas (e.g. that you should test your beliefs) but it leads to a radically different picture of the world (e.g. quantum mechanics). Likewise, effective altruism is based on simple ideas – that we should treat people equally and it’s better to help more people than fewer – but it leads to an unconventional and ever-evolving picture of doing good.

How can you take action?

People interested in effective altruism most often attempt to apply the ideas in their lives by:

-

Choosing careers that help tackle pressing problems, or by finding ways to use their existing skills to contribute to these problems, such as by using advice from 80,000 Hours.

-

Donating to carefully chosen charities, such as by using research from GiveWell or Giving What We Can.

-

Starting new organizations that help to tackle pressing problems.

-

Helping to build communities tackling pressing problems.

The above are not exhaustive. You can apply effective altruism no matter how much you want to focus on doing good, and in any area of your life – what matters is that, no matter how much you want to contribute, your efforts are driven by the four values above, and you try to make your efforts as effective as possible.

Typically, this involves trying to identify big and neglected global problems, the most effective solutions to those problems, and ways you can contribute to those solutions – with whatever time or money you’re willing to give.

By doing this and thinking carefully, you might find it’s possible to have far more impact with those resources. It really is possible to save hundreds of people’s lives over your career. And by teaming up with others in the community, you can play a role in tackling some of the most important issues civilization faces today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Footnotes

-

You can see the global distribution of local EA groups on the Effective Altruism Forum, which lists groups in over 70 countries. ↩

-

The less neglected an issue, the more the best opportunities will have been taken, so the harder it will be for an additional person to make an impact.In fact, there are good reasons to expect that returns to investment in an issue are roughly logarithmic.Logarithmic returns imply that if 10 times more has been invested in one cause compared to another, then additional resources will achieve about 1/10 as much progress.If the two issues are equally important, and then an additional person working on the more neglected one will have ten times the impact. ↩

-

From 2010 to 2019, US Federal Funding for Health Security is estimated at $141 billion. We judge that 55% of this was spent on what could arguably prevent future pandemics. For example, 4% was spent tackling the ongoing ebola epidemic, which provided infrastructure for potential other pandemics. However, 17% was spent on chemical and nuclear radiation threats in a way unlikely to affect future pandemic spread.141 billion * 0.55 = 79 billionAnnualized over the ten year period is $8 billion per year.Federal funding for health security in FY2019 Watson, Crystal, et al., Health security 16.5 (2018): pages 281-303. Archived link, accessed 5 March 2020.Open Philanthropy also identifies other foundations and philanthropists working on the topic prior to the COVID pandemic, which we believe total under $100 million in funding.Crawford, director of the Costs of War project, calculates US spending on Counter-Terrorism from 2001-2022 to be $5.8 trillion.5.8 trillion / 20 years = $290 billion per year.United States budgetary costs of Post-9/11 wars Crawford, Neta C., Watson Institute for International & Public Affairs, Brown University, 2021. Archived link, accessed 26 July 2022. ↩

-

Deaths from terrorism from 1970-2020 were approximately 456,000. This is from the Global Terrorism Database 2020, accessed 11 August 2022.Note that Our World in Data says "The Global Terrorism Database is the most comprehensive dataset on terrorist attacks available and recent data is complete. However, we expect, based on our analysis, that longer-term data is incomplete (with the exception of the US and Europe). We therefore do not recommend this dataset for the inference of long-term trends in the prevalence of terrorism globally."This means the source above is likely an undercount of confirmed terrorism deaths; however, even if we assume deaths have been at the same level as the highest recorded decade (2010-2020) since 1970, the total deathtoll would still only be 1.2 million; far less than deaths due to pandemics.Deaths from COVID-19:The Economist estimated cumulative excess deaths due to COVID-19 were 21.47m as of June 2022, and this amount is still rising.You can see this data and their model through Our World in Data (archived page, retrieved 28 July 2022).We see this as the best current estimate of COVID-19’s total death toll. The number of confirmed deaths is lower, at around 6 million, but this excludes deaths that were indirectly caused or weren’t reported. The Economist’s methodology compares excess deaths to the seasonal average, to estimate in total how many additional people died, and adjusts for underreporting.Deaths due to pandemics and terrorism are both heavy tailed, so past death rates will typically understimate the magnitude of the risk.For instance, it’s possible that terrorists could set off a nuclear weapon in a large city, which might kill over 1 million people. This didn’t happen over the last fifty years, but would have been the main driver of the death toll if it had. And likewise, there could have been a pandemic much worse than COVID-19 or HIV/AIDS in the last 50 years.The key question then becomes whether the historical record is a greater undercount of the risk for terrorism or for pandemics (i.e. whether terrorism deaths are more heavily-tailed than pandemic deaths).It seems plausible that the worst case scenario from pandemics is worse than for terrorism. There’s nothing to rule out the emergence of a pandemic that’s more infectious than COVID-19, but with a fatality rate of 10-50%, or worse. And there seem to be more near-misses in the historical record.So, the problem of missing tail events in the sample may well be worse for pandemics than terrorism. Indeed, the most plausible way for terrorism to kill 1+ billion people is probably via causing a pandemic.Given that terrorism receives ~100x more funding than pandemic prevention, while pandemics seem to have caused 10-100x more deaths historically, the corrections would need to be very heavily in favour of terrorism in order for the current allocation of resources to seem more balanced.The above analysis was just in terms of the number of deaths, since that’s an important yet relatively measurable metric. Deaths due to both pandemics and terrorism also produce important indirect costs, and a fuller comparison would attempt to consider the relative scale of each. ↩

-

↩“40.1 million [33.6 million–48.6million] people have died from AIDS-related illnesses since the start of the epidemic.” Global HIV & AIDS statistics — Fact sheet UNAIDS, 2022. Archived link, accessed 11 August 2022. -

Open Philanthropy is a foundation inspired by effective altruism. They first funded the Johns Hopkins Centre for Health Security (CHS) in 2016. This was followed by several other large grants, including one for $16m in 2017 and another for $19.5m in 2019. ↩

-

38,659 volunteers, as of 7 July 2022. 1Day Sooner ↩

-

Before COVID-19, the number of people living on less that $1.90 per day had decreased to 689 million in 2017. However, estimates now point to the first rise in the extreme poverty rate since 1998, leading to an estimated 731 million people now living on less than $1.90 per day.UN SDG 1 - End poverty in all its forms. UN Statistics, 2022. Archived link, accessed 26 July 2022.These estimates have been adjusted for the fact that money goes further in poor countries (purchasing parity). There are many complications to the estimates, but it’s clear that hundreds of millions of people live at near subsidence levels of income. See “how accurately does anyone know the global distribution of income?” if you’d like to learn more. ↩

-

The US poverty line for 1 person is an annual income of $13,590.13,590 / 365 = $37.23 per day.This is 20x the international poverty line of $1.90, which is adjusted for purchasing parity.According to the 2019 census, full-time workers aged 25-65 with a college degree or higher earned a median of $74,000 per year.$74,000 / 365 = $202.7 per day$202 / 1.9 = 107x.According to SmartAsset, a single person household earning $74,000 pre-tax and living in New York, receives about $53,000 post-tax.According to Giving What We Can’s calculator, a post-tax income of $53,000 puts you in the top 1.3% of income globally. ↩

-

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends spending up to £30,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained, where the intervention is reliable.“Above a most plausible ICER of £30,000 per QALY gained, advisory bodies will need to make an increasingly stronger case for supporting the intervention as an effective use of NHS resources” Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance. UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, September 2012. Archived link, accessed July 28, 2022.It’s typical in global health to say that saving one life is equivalent to 30 QALYs. Source: World Bank (Box 1.1)This amounts to a cost of saving a life of 30 x £30,000 = £900,000 = $1.1 million.In the US, different global agencies estimate “the value of life”, and use this figure in the prioritization of different spending projects. The Federal Emergency Management Agency estimated the value of life at $7.5 million in 2020. This estimate has fluctuated based on the context. For example, the US Department of Transport estimated the value of life to be between $5.2 million and $13.0 million in 2014. ↩

-

GiveWell's estimates of the cost to save a life have varied over time (depending on their research, and which opportunities are available), but have typically fallen within $2,500 to $7,500. In 2021, GiveWell estimated that $5500 spent on distributing insecticide-treated bednets will save one life in expectation.You can see their most up-to-date estimates in their full cost-effectiveness analysis: How We Produce Impact Estimates GiveWell, July 2022. Archived link, accessed 28 July 2022. ↩

-

↩“More than 110,000 donors have trusted GiveWell to direct their donations. Together, they have given over $1 billion to the organizations we recommend. These donations will save over 150,000 lives and provide cash grants of over $175 million to the global poor.” About GiveWell, GiveWell, July 2022. Archived link, accessed 28 July 2022. -

↩“When Wave launched in Senegal, our average transfer would have cost 3-5x more if done via the largest existing mobile money system. Multiplied by our millions of monthly active users, that comes out to a savings of over $200 million every year, … around 1% of Senegal’s GDP.” Working at Wave is an extremely effective way to improve the world. Ben Kuhn, July 8 2021. Archived link, accessed 26 July 2022. -

Conversation: "Our best end-to-end trained Meena model achieves a… SSA [Sensibleness and Specificity Average] score of 72%... our SSA score of 72% is not far from the 86% SSA achieved by the average person.” Towards a Conversational Agent that Can Chat About…Anything. Adiwardana et. al., Google, 28 January 2020. Archived link, accessed 28 July 2022.Math: The graphs in the attached article show Google’s Minerva accurately answers over 50% of “high school math competition-level problems”. Other state-of-the-art models were achieving less than 10% accuracy.Minerva: Solving Quantitative Reasoning Problems with Language Models. Dyer et. al, Google, 30 June 2022. Archived link, accessed 28 July 2022.Jokes: Google’s AI PaLM can provide explanations for jokes never seen before, including jokes nowhere on the internet. For example:“Joke: Did you see that Google just hired an eloquent whale for their TPU team? It showed them how to communicate between two different pods!Explanation: TPUs are a type of computer chip that Google uses for deep learning. A ‘pod’ is a group of TPUs. a ‘pod’ is also a group of whales. The joke is that the whale is able to communicate between two groups of whales, but the speaker is pretending that the whale is able to communicate between two groups of TPUs”Pathways Language Model (PaLM): Scaling to 540 Billion Parameters for Breakthrough Performance. Narang et. al., Google, 4 April 2022. Archived linkImages: Example images from OpenAI’s Dall-E 2 can be seen here.Coding: Section 3.1 in Salesforce’s ‘A Conversational Paradigm for Program Synthesis‘ research paper about CodeGen, their AI tool turning human instructions into code, outlines that CodeGen achieves a 75% HumanEval score, meaning it can solve 75% of the programming challenges described with normal human language in the HumanEval set. ↩

-

It’s difficult to estimate the number of researchers focused on a certain topic since it’s hard to define the topic in the first place, many researchers work on multiple topics, and it’s hard to know the bar for ‘being a researcher’. So these numbers should be understood as estimates to within a factor of three or so, and they could be out by an order of magnitude depending on some interpretations of the question.In 2020, 87,000 authors published AI research on arXiv. The 2020 Global AI Talent Report from Element AI estimates there are even more people than this working on AI development globally, with 155,000 people labelled on social media as working in AI research or engineering. However we expect some working in AI engineering to not be working on engineering new advancements in AI. We have taken the smaller estimate of 87,000 and roughly halved it for an estimate of 40,000.In 2021, Gavin Leech estimated that 270 to 830 FTE people worked on AI Safety. However, the upper end of the range of this estimate is based on what we think is an overly broad notion of what constitutes research into AI alignment, and much of the sum was driven by adding up time from lots of researchers spending a small fraction of their time on safety research; while our aim is to quantify the number of researchers focused on AI safety.AI Watch attempted a headcount of AI Safety researchers, which found 160 notable researchers who have worked on AI Safety. This includes many people who have not published on AI safety in over a year, whereas for the estimate of 87,000 above, all had published in the last year. On the other hand, the bar for being a ‘notable’ researcher might be higher than publishing in arXiv.Our final estimate is 300 researchers focused on AI safety. ↩

-

In 2018, 9.56 billion farm animals were slaughtered for meat in the US. This number has likely risen since then. This includes 9.16 billion chickens; 237 million turkey; 125 million pigs; 34 million cattle and 2 million sheep. Source: visualization at Our World in Data, using data from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. ↩

-

In 2021, approximately 6.5 million animals passed through animal shelters in the US. In 2011, this number was 7.2 million. Assuming a steady decline, this means in 2018 there were approximately 6.7 million animals passing through animal shelters.9.56 billion / 6.7 million = 1427 times as many animals in factory farms.Pet Statistics. American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, 2021. Archived link, accessed August 2021. ↩

-

Animal shelter spending:Andrew Rowan calculated $5 billion of funding to the top 3000 animal shelter organizations in the US in 2018, published in his paper “Cat Demographics & Impact on Wildlife in the USA, the UK, Australia and New Zealand: Facts and Values” Rowan et. al. (2020), Journal of Applied Animal Ethics Research, pages 7–37.Andrew Rowan confirmed the data behind these calculations in correspondence with us.Farm animal advocacy funding:Research from Open Philanthropy published here finds the following funding for farm animal advocacy groups in 2018:

- $32.3 million for Established US groups (PETA, PCRM, HSUS, ALDF, ASPCA)

- $32.6 million for new, major US-based groups (CIWF, WAP, RSPCA, HSI)

- $32.2 million for all other US groups

32.3 + 32.6 + 32.2 = $97.1 million ↩ -

106.5 million hens are now in cage-free housing in the US alone as of May 2022, as reported by the USDA Egg Markets Overview, compared to 17 million in 2016. We believe another 100 million have become cage-free in Europe as a result of Open Wing Alliance’s work, although this number is harder to attribute to them specifically.In addition, advocates have now secured corporate pledges that, if implemented, should cover more than 500 million hens alive at any time. ↩

-

After engagement with GFI, the US government announced a $10 million grant to create a center of excellence in cellular agriculture at Tufts University. The UK’s independent National Food Strategy recommended a £125 million investment in alternative protein research and innovation. Source: GFI Year in Review 2021 (page 3) ↩

FAQ

Who created this website and why?

This website was created by the Centre for Effective Altruism, a charity dedicated to building and nurturing the effective altruism community. We created this website to help explain and spread the ideas of effective altruism.

What is the definition of effective altruism?

Effective altruism is the project of trying to find the best ways of helping others, and putting them into practice.

We can roughly break the project of effective altruism down into a research field that aims to identify the most effective ways of helping others, and a practical community of people who aim to use the results of that research to make the world better.

Someone is practising effective altruism if they’re participating in either of these two projects i.e. attempting to find more effective ways of helping, or devoting some of their resources to the most effective ways of helping discovered so far.

Effective altruism, defined in this way, doesn’t say anything about how much someone should give. What matters is that they use the time and money they want to give as effectively as possible.

“As effectively as possible” means trying to uphold the four values of effective altruism covered above: (i) prioritization – trying to weigh the scale of the effects of your actions (ii) impartial altruism – attempting to treat others equally (iii) truthseeking – constantly searching for new evidence and arguments (iv) collaborative spirit – acting with high standards of honesty and friendliness, and taking a community perspective.

What is meant by “helping others” or “doing good” within effective altruism? See the next FAQ entry.

To see a more precise definition of effective altruism, see The Definition of Effective Altruism.

What is meant by ‘doing good’ or ‘helping others’ in effective altruism?

What it means to ‘do good’ is a subject of active debate and research in the community, which includes people who hold many different moral views.

That said, typically in effective altruism, ‘doing good’ is tentatively understood to mean enabling others to have lives that are healthy, happy, fulfilled; in line with their wishes; and free from avoidable suffering – to have lives with greater wellbeing.

Effective altruism has this focus because increasing wellbeing is a goal that is important to many people. That isn’t to say that only increasing wellbeing matters, and in practice people in effective altruism have many other values.

Because what matters morally is so uncertain, people involved in effective altruism aim to respect other widely held values in their pursuit of doing good. Effective altruism is not about “ends justifies the means” thinking. It is about being a good citizen while ambitiously working toward a better world.

Read more about how 80,000 Hours – a non-profit that’s part of the community – defines ‘doing good’ here.

To see a more precise definition of doing good used in effective altruism, see The Definition of Effective Altruism, by the philosopher and co-founder of Effective Altruism, William MacAskill.

How did effective altruism get started?

Effective altruism was formed when several communities around the world came together, including Giving What We Can and the Future of Humanity Institute in Oxford, the rationality community in the Bay Area, and GiveWell (then in New York).

The term ‘effective altruism’ was coined in Oxford in 2011 as part of the name for the Centre for Effective Altruism (which hosts this website), but it caught on as a term to describe the broader movement.

Some of effective altruism’s intellectual inspirations are evidence-based medicine & policy; applied utilitarianism; and research into heuristics and biases in human reasoning.

Here is a talk about the intellectual history of effective altruism by Toby Ord and a history of the term ‘effective altruism’.

What resources have inspired people to get involved with effective altruism in the past?

Some examples of resources that have inspired people to get involved in effective altruism (but don’t necessarily represent its current form) include:

- Doing Good Better, by Will MacAskill

- The 80,000 Hours career guide, by Benjamin Todd

- The Precipice, by Toby Ord

- Taking Charity Seriously, by Toby Ord

- Our top charities, by GiveWell

- An introduction to effective altruism, by Ajeya Cotra

- Rationality: A-Z, by Eliezer Yudkowsky

- Doing Good – A conversation with William MacAskill, by Sam Harris

- The why and how of effective altruism, by Peter Singer at TED.

- The Drowning Child and the Expanding Circle, by Peter Singer

- On Caring, by Nate Soares

- The most important century, by Holden Karnofsky

- 500 million, but not a single one more, by Jai Dhyani

- Animal Liberation, by Peter Singer

- Effective altruism: an introduction, the 80,000 Hours podcast

Why does effective altruism matter?

In brief:

- Lots of people want to do good.

- Some ways of doing good achieve much more than others (given the same amount of resources).

- These differences are not widely known or acted upon.

This means that by searching for the most effective ways to do good, making them widely known, and acting on them, people interested in doing good can do far more to tackle the world’s most pressing problems.

Moreover, this can be achieved even if the amount of resources devoted to doing good doesn’t increase.

What do people interested in effective altruism work on in practice?

People interested in effective altruism work on a wide range of issues and projects.

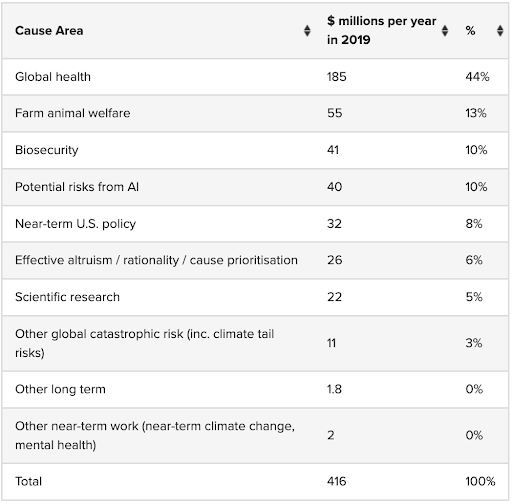

For instance, Benjamin Todd estimated the following distribution of funding across issues in 2019:

In terms of how they contribute, many choose jobs with the aim of tackling pressing problems. These jobs span all sectors, including within non-profit and for-profit organisations aiming to tackle these problems, academic research, or positions in government and policy.

Over 5,000 people pledge to donate over 10% of their income to the charities they believe are most effective through Giving What We Can, and over 100,000 people have made at least one donation based on GiveWell’s recommendations.

A common misconception is that effective altruism is only about donating money to global health charities or ‘earning to give’. But community members support many causes besides global health, only a minority are prioritizing earning to give, and effective altruism is as much about how to use your time effectively as your money. In fact, the organization 80,000 Hours argues that for many people, their career decisions matter more than their decisions about where to donate. Read more in “Misconceptions about effective altruism”.

See examples of people practising effective altruism in the next question.

What are some examples of people involved in effective altruism?

See some examples of:

Does effective altruism say I should make doing good my only focus in life?

No. How much to focus on doing good is a personal decision.

Effective altruism is about how to use the resources you want to devote to doing good as effectively as possible, not how much to focus on helping others in the first place.

Effective altruism often inspires people to make doing good a greater focus, because they realise it’s possible to do more good than they thought.

But for most in the community, doing good is just one important goal among several moral and personal goals. Likewise, while some in the community donate 50%+ of their income to charity, others only donate 1%.

Your own decision will be based partly on your moral views, and partly on your life circumstances. Many are simply not able to make helping others a major focus in life.

Even if you do want to make doing good a major focus, making it your only focus is often counterproductive. First, this is because what matters morally is deeply uncertain, and focusing on one ill-defined moral goal to the exclusion of all others could easily cause harm. Second, having a single goal isn’t a good match with most people’s psychology, so is likely to cause burnout, reducing your impact in the long term.

Why don’t people in effective altruism focus on more conventional issues?

A key consideration for which issue one should focus on is where resources are already being allocated by society. If an important problem is already widely recognised, then it is likely that a lot of people are already trying to solve it. That means it will usually be harder for a few extra people who decide to work on the issue to have a very large impact. All else equal, it’s possible to do far more good in an area that is not getting the attention it deserves.

One way to think about this is in terms of a "world portfolio" – what would the ideal allocation of resources be across all social causes? And where are we farthest from that ideal allocation?

This is why the issues people in effective altruism prioritize can seem surprising or narrow. They focus on the issues that are furthest from getting the attention they need.

This means the issues the community focuses on will change over time. If more people get interested in effective altruism, then the issues focused on today will no longer be neglected, and the community will change or expand its scope.

Where do organizations inspired by effective altruism get their funding?

Some organizations in the community are backed by a large number of individual effective donors. For example, over 110,000 individual donors have used GiveWell’s research to contribute more than $1 billion to its recommended charities. Others — including the Centre for Effective Altruism, which produced this website — are supported in significant part by grantmaking organizations inspired by effective altruism such as Open Philanthropy. Grants and donations can vary widely in size; the common thread between them is that these donors care deeply about doing as much good as possible with their giving.

Common objections to effective altruism

Is effective altruism only about making money and donating it to charity?

In the past, the community made the mistake of becoming too closely associated with “earning to give”. Many people involved in effective altruism still think this is a good strategy for some people, particularly those who have a good personal fit for high-paying careers. But donating to charity is not the only way to have a large impact. Many people can do even better by using their careers to help others more directly. Many people in the community do both.

We still believe that donating to the right charities is one way you can make a lot of difference. It’s also one where there’s relatively strong evidence available, because there was existing research to build on.

Read more:

- How you can help others with your career

- How you can help others by donating to the most effective charities

- Should you “earn to give”?

Examples of this objection:

- Lisa Herzog in openDemocracy

- Jennifer Rubenstein in the Boston Review

- Sam Earle and Rupert Read in the Ecologist

Is effective altruism the same as utilitarianism? What if I’m not a utilitarian?

Utilitarians are usually enthusiastic about effective altruism. But many effective altruists are not utilitarians and care intrinsically about things other than welfare, such as violation of rights, freedom, inequality, personal virtue and more. In practice, most people give some weight to a range of different ethical theories.

The only ethical position necessary for effective altruism is believing that helping others is important. Effective altruism doesn’t necessarily say that doing everything possible to help others is obligatory, and doesn’t advocate for violating people’s rights even if doing so would lead to the best consequences.

Read more:

Examples of this objection:

- Iason Gabriel in the Boston Review

- Catherine Tumber in the Boston Review

Does effective altruism neglect systemic change?

Some people think effective altruism is too concerned with ‘band-aid’ solutions like direct health interventions without seriously challenging the broader systemic causes of important global issues. Many people believe unfettered capitalism, wealth inequality, consumer culture, or overpopulation contribute significantly to the amount of suffering in the world, and that attempts to make the world better that don’t address these root causes are meaningless or misguided.

It’s certainly true that effective altruism is interested in approaches that are ‘proven’ to work, such as scaling up rigorously tested health treatments. These provide a good baseline against which we can assess other, more speculative, approaches. However, as we get more skilled in evaluating what works and what doesn’t, many in the community are shifting into approaches that involve systemic change.

It’s important to remember that opinions are heavily divided on whether systems like trade globalization or market economies are net negative or net positive. It’s also not clear whether we can substantially change these systems in ways that won’t have very bad unintended consequences.

This difference of opinion is reflected within the community itself. Effective altruism is about being open-minded — we should try to avoid being dogmatic or too wedded to a particular ideology. We should evaluate all claims about how to make a difference based on the available evidence. If there’s something we can do that seems likely to make a big net positive difference, then we should pursue it.

Read more:

- Why many in the community focus on systemic change

- Evaluations of policy areas addressing systemic issues

- GiveWell's move toward research on systemic change

Examples of this objection:

- Sam Earle and Rupert Read in the Ecologist

- Iason Gabriel in Journal of Applied Philosophy

- Amia Srinivasan in London Review of Books

- Mathew Snow in Jacobin

If everyone followed the advice of effective altruism, wouldn’t that lead to a misallocation of resources?

If everyone took the same action, and never updated their views in response to changing circumstances, then yes, that would create problems. Effective altruism makes recommendations about the best available opportunities to help, taking what other people are already doing into account.

As more people take the opportunities we recommend, they will stop being so neglected, and the value of allocating more resources to them will go down. At that point we would change our recommendations to encompass other opportunities. This is still very far away.

Read more:

Examples of this objection:

- Gary Steuer in Washington Post

Is effective altruism calculating and impersonal?

Effective altruism is about taking a desire to do good, but using reason and evidence to guide our actions so we have the greatest chance of success. It’s true that this sometimes involves calculations of how effective certain actions might be. It’s also true that we don’t always know the people we are assisting.

Most people are drawn to effective altruism because they have a high level of compassion towards others, and think that we should help others regardless of whether we know them personally. In order to do this the most effective way, it’s sometimes important to make calculations.

Read more:

- Why effective altruism is calculating, but not cold

- How compassion can inspire us to help those we’ve never met

Examples of this objection:

- Ken Berger & Robert Penna in Stanford Social Innovation Review

- Emma Goldberg in the New York Times

Is effective altruism too demanding?

The lengths an individual should go to when attempting to make the world a better place is a difficult, personal question. But many people interested in effective altruism give 10% or more of their income, and/or shift your career path in order to have substantially more social impact.

For some, that might seem like a big sacrifice. But for many, spending your life working to improve the world provides a clear goal and a strong sense of purpose, and effective altruism provides a friendly, global community to collaborate with. Trying to help others as much as possible can be more purposeful, fulfilling and maybe even more fun, than any of the alternatives.

There’s nothing desirable about sacrifice in and of itself. You certainly don’t have to give up the things that make you happy, or neglect your personal relationships. The point is to help others, not to make yourself feel bad.

Read more:

Examples of this objection:

- Tom Farsides in The Psychologist

Doesn’t charity start at home?

Many people agree that we should try to make a difference, but think that we should give our money or our time to people in our local communities.

There’s nothing bad about helping people you know, or even yourself. But often the opportunities to help people far away are far greater than the opportunities to help people near you, especially if you live in a wealthy country.

For example, it costs about $40,000 to train a guide dog to be an effective help to a blind person in the US. The cost of curing trachoma in a developing country is between 25 and 50 dollars, meaning $40,000 could also cure between 400 and 2000 people of blindness.

Read more:

Examples of this objection:

- David Brooks in the New York Times

Does charity and aid really work?

A lot of charity work is ineffective, and there are many examples of aid and development having no real impact. But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t some charities which achieve amazing outcomes. In fact, that’s exactly why it’s so important to find the best ones, and use our best judgement when working out which causes we should spend money and time supporting.

There are also many other opportunities to have a big impact, including for-profit entrepreneurship, policy, politics, advocacy, and research.

Read more:

Examples of this objection:

- Angus Deaton in the Boston Review

Does donating to charity just subsidize billionaires?

It’s plausible that if individuals stopped donating to the most effective charities, larger philanthropic organizations would step in to fill the gap. So, in the end, the effect of the individual donations would just be to free up money for the larger philanthropic organizations.

This is a difficult question to resolve. On the one hand, it’s likely that, if individual donors didn’t exist, larger donors would take up some of the slack. On the other hand, if money is freed up for large and effective philanthropic organizations, they can then fund other effective interventions, including those that are important but that individual donors would be less likely to support.

But there are some highly effective charities which can productively absorb a lot more funding. For instance, in 2018, GiveDirectly transferred more than $30 million to the poorest people in the world, and they could transfer far more money if they received more donations. Donating to charities with a large funding gap is less likely to displace funding from others sources.

Hundreds of billions of dollars will be needed to fund effective interventions in the next fifteen years. This gap cannot be fully covered by big foundations. For example, Good Ventures and the Gates Foundation have endowments of around $8bn and $41bn respectively.

As above, if you’re skeptical about donating to charity, then there are many other ways that you could use the principles of effective altruism to help you make a difference more effectively, such as helping you to choose which cause to work on.

Examples of this objection:

How are the people you’re trying to help involved in the decision-making?

The possibility that we don’t actually understand and address the needs of the people we are trying to help is real, and a risk we have to remain constantly vigilant about. If we don’t listen to or understand recipients we will be less effective, which is the opposite of our goal.

Some people support the charity GiveDirectly because it gives cash to people in poverty, leaving it entirely up to them how they spend the money. This might empower people in poverty to a greater extent than choosing services that may ultimately not be desired by the local community.

Other charities we support provide basic health services, such as vaccinations or micronutrients. These are so clearly good that it’s very unlikely the recipients wouldn’t value them. Better health can empower people to improve aspects of their own circumstances in ways we as outsiders cannot.

In cases where the above don’t apply, we can conduct detailed impact evaluations to see how the recipients actually feel about the service that purports to help them. Of course, such surveys won’t always be reliable but they’re often the best we can do.

In other cases, such as when we’re trying to help non-human animals or future generations, these issues can be even more difficult, and people do their best to predict what they would want if they could speak to us. Obvious cases would include pigs not wanting to be permanently confined to ‘gestation crates’ in which they cannot turn around, or future generations not wanting to inherit a planet on which humans cannot easily live.

Read more:

Examples of this objection:

- Angus Deaton in the Boston Review

- Jennifer Rubenstein in the Boston Review

- Cecelia Lynch in CIHA

Does effective altruism neglect effective interventions when the impact can’t be measured?

Some of the actions that we recommend are ones that have been tested and shown to have a high impact. But there are many actions that seem promising which would be infeasible to evaluate using experimental methods such as randomised controlled trials. However, when high-quality evidence is available, we take it very seriously.

Several organizations inspired by effective altruism work on more ‘speculative’ projects, which are very difficult to quantify. For example, Open Philanthropy Project works on immigration reform, criminal justice reform, macroeconomics, and international development.

Read more:

Examples of this objection:

- Emily Clough in the Boston Review

- Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry in The Week.

Is the effective altruism community too homogeneous?

The effective altruist community could benefit from being more diverse. The community first emerged among people in richer nations and at key universities, but as it grows, it’s drawing in people from many different backgrounds. We’ve been excited to see cities across the globe hosting EA conferences, from Subgabire to Abuja, Nigeria.

In terms of our beliefs and practices, we’re very diverse. Some are vegetarians, others aren’t. The community as a whole is secular, but some members are religious. And there’s a wide range of political beliefs. While many people have strongly-held beliefs and values, there is a strong emphasis on building a community that is respectful of difference, and open to listening to criticism. What unites us is a shared passion for helping others as much as possible.

Read more:

What’s next?

If you’re interested in learning about how to do more good, here are some next steps

Join 60k subscribers and sign up for the EA Newsletter, a monthly email with the latest ideas and opportunities